November 23, 2020

Risk and Return

Who is the Biggest Investor in the Stock Market, and Why Should You Care?

By Victor Haghani and James White 1

The US Treasury effectively “owns” about 24% of the stocks held by high income US taxable investors. Through the capital gains tax, Uncle Sam has an effective exposure of more than $1 trillion of equities.2 And this huge-but-silent investor might be about to get a lot bigger if capital gains taxation is increased. But it’s not all bad news; luckily there is something you can do to lessen the blow. In this note, we’ll explain how adjusting your asset allocation to account for capital gains taxation can improve your after-tax expected welfare.

Last month, we wrote about a framework for deciding how much to accelerate the realization of capital gains if tax rates are likely to increase. The idea is to maximize your Expected Risk-Adjusted Wealth, which can often lead to a different decision than one based solely on the ‘static’ analysis of the single most likely scenario.3 Linked to the decision of how much to accelerate is the question of how capital gains taxation impacts how much risk to take, which is the question we address in this note. Throughout this note, we’ll more generally use equities as a proxy for risky assets.

The primary take-aways for long-term investors are:

- increases in the capital gains tax rate often (but not always) lead to higher optimal equity allocations,

- in general, investors should respond to changes that increase the bite of capital gains tax, such as higher inflation or larger embedded unrealized gains, by increasing their exposure to equities,

- for a given dollar amount of expected tax, capital gains taxation is the kindest form it can take, as it reduces Expected Risk-Adjusted Wealth less than alternatives such as income or wealth taxes.

The optimal risk decision for a taxable investor is a function of too many variables to be reducible into a rule-of-thumb, which is why we have provided a calculator you can use along with the note.

You can find our Decision Calculator here.

You can find the math and code behind the framework here.

The Impact of Capital Gains Tax on the Optimal Allocation to Equities

Let’s start with looking at whether a higher future capital gains rate should change how much to allocate to equities, which we expect to generate capital gains in the future but may also generate capital losses. Happily, there’s a long history of economists studying the effect of capital taxation on risk-taking. Economists have noted that if the government applied capital gains taxation symmetrically to gains and losses, then investors shouldn’t care about the tax rate at all; they would simply respond to increases in tax rates by increasing their exposure to the risky asset so as to keep the post-tax expected return constant.4

Unfortunately, we don’t live in a world of symmetric taxation, and it’s unlikely we’ll wake up in that world any time soon. Instead, we’re taxed on realized gains, with realized losses creating a tax-loss carry-forward credit which can only be used against future realized gains.5 But understanding how things would work in the symmetric case is a good starting point for investors with very long horizons and/or who hold assets that are very appreciated versus their cost basis.

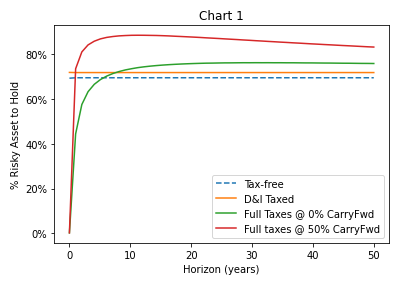

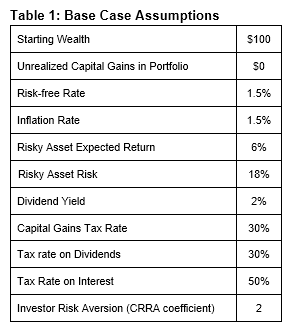

To fully answer the question of how the capital gains tax rate should impact an investor’s risk-taking, we’ll again reach for our Risk-Adjusted Wealth Maximization tool, which we used to crack the problem posed in our To Realize or Not To Realize note. We’ll assume market expected returns and risk as set out in Table 1, such that in a zero-tax world our hypothetical investor (with a standard level of risk aversion) would maximize their Expected Risk-Adjusted Wealth by choosing a 70% equity/ 30% bond allocation.6 Then, for any given set of tax rates, investment horizon and initial unrealized gains, we can find the optimal allocation to equities that results in the highest expected Risk-Adjusted Wealth. In Chart 1, we compare the optimal allocation to equities as a function of horizon, under four taxation assumptions:

- no taxation at all (dotted blue)

- taxation of interest at 50%, dividends at 30% and capital gains at 0% – for investors expecting to avoid paying capital gains tax completely (orange)7

- taxation of interest at 50% and dividends and capital gains at 30%, with no value on loss carry-forwards (green)

- taxation of interest at 50% and dividends and capital gains at 30%, with 50% value on loss carry-forwards (red)

If only interest and dividends are taxed, the optimal allocation to equities would be just a bit higher than in the no-taxation case. This is because, with our Base Case assumptions, taxing dividends reduces equity returns by slightly less than taxing interest reduces the return on the risk-free asset, making equities look slightly more attractive after-tax. When we introduce taxation of capital gains (the red and green lines) for investment horizons greater than 10 years, we see the predicted result of a higher optimal allocation to equities – although the effect is not as large as it would be in the pure symmetric case.

At horizons under 10 years, the presence of capital gains tax causes our investor to want a smaller equity allocation than in a tax-free world, if they place no value on loss carry-forwards. To see why, we can think of capital gains tax as being a call option sold for free by the investor to the government. For short horizons, the value of the call option takes a big chunk out of the expected return offered by equities, so owning less is optimal.8 As the horizon lengthens, the optionality of the capital gains tax liability decreases as a per annum cost and the benefit of deferring the payment of the tax increases, resulting in an increasing optimal equity allocation. Figuring out exactly what is optimal for a given investor will depend significantly on how they value the potential tax-loss carryforward that may arise from a realized loss.9

Sizing Up the Impacts of Taxation

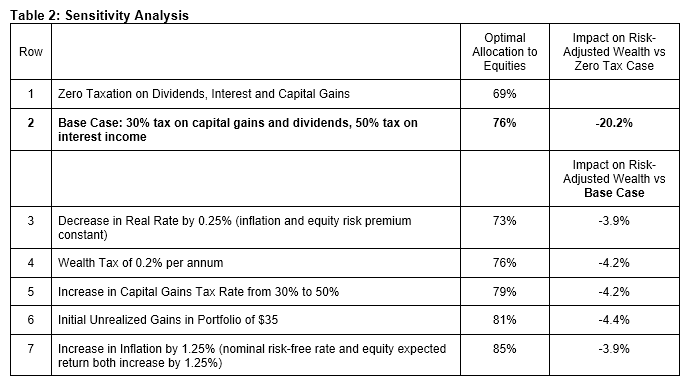

In the idealized world from econ 101, with only a risk-free and a risky asset to choose from, no taxation, no transactions costs and asset prices that follow random walks, an investor’s optimal allocation to the risky asset is a function of just three variables: the risky asset’s excess expected return, its risk, and the risk-preferences of the individual. When we bring taxes into the problem, the optimal asset allocation becomes a function of many variables we can ignore in the zero-tax world. In Table 2 below, we use our tax calculator to see how the optimal allocation to equities changes based on changes in a range of variables, and also how these changes affect investor welfare. We use the assumptions in Table 1 as the Base Case, with a 20-year horizon.

For an investor starting out with large unrealized gains in their portfolio (row 6), we find that a larger equity allocation of 81% is optimal.10 The increase in the optimal allocation to equities that results from higher unrealized gains suggests that as the market goes up, assuming expected returns remain the same, investors should want to increase their exposure to the market. The framework also suggests, as shown in row 5, that an increase in the capital gains tax rate should lead taxable, long-term investors to want to increase their allocation to equities, a conclusion that may run counter to the analysis of many market observers who view an increase in the capital gains rate as making equities less attractive. Of course, both of these effects are predicated on investors thinking about the impact of capital gains taxes in a framework similar to the one we are proposing, and the impact on markets will be driven by the characteristics of marginal investors who may look quite different from our long-term, taxable, utility-maximizing exemplar.

In the rightmost column of the table, we can see that an increase in the capital gains tax rate from 30% to 50% (row 5) is roughly equivalent to the harm caused by each of the following:

- An increase in unrealized gains in the portfolio of $35 per $100

- An increase in inflation of 1.25%11

- A decrease in the risk-free real rate of 0.25%

- A wealth tax of 0.2% per annum

Perhaps most surprising of these observations is the last one, that a 0.2% wealth tax decreases a long-term investor’s welfare as much as an increase in the capital gains tax from 30% to 50%, even though a 20% increase in capital gains tax would result in about three times as much expected taxes paid over the 20-year horizon as the wealth tax.12 There are two reasons for this surprising equivalence: 1) the capital gains tax is paid at the end of 20 years while the wealth tax payments are spread out over the whole period, and 2) more significantly, the capital gains tax is paid only when the investments have done well, whereas the wealth tax is owed regardless. The same reasoning explains why just a 0.25% decrease in the risk-free real rate does the same harm to our investor’s welfare as a 20% hike in the capital gains tax rate. It is sobering to realize that the 4% drop in long-term US TIPS yields over the past 20 years has done far more damage to the welfare of current investors than any possible change to the long-term capital gains tax rate could inflict.

Conclusion

The taxation of investment income and capital gains not only reduces the welfare of individual investors relative to a world of zero taxes on our savings (ignoring possible societal benefits of the taxes collected), but it also can materially affect our asset allocation decisions. Capital gains tax, due to its character as a one-sided tax, requires a framework that takes account of risk in outcomes and an investor’s personal risk-aversion. It is also notable that the level of real interest rates and inflation have a material impact on both our risk-adjusted wealth and our tax-adjusted optimal asset allocation.

From Table 2, we see that almost every change that hurts investor welfare is also associated with an increase in the optimal allocation to equities. In general, the greater allocation to equities softens the blow from the taxman taking a bigger slice of the investor’s pie.

We encourage you to spend some time with our calculator, and please do get in touch with us if you’d like to discuss how this framework might be applied to your individual circumstances and decisions.

Disclaimer:

In this note, we’ve provided a framework for thinking about tax-related investment decisions. Nothing in this note should be construed as tax advice pertaining to any individual’s specific circumstances, and your authors are not tax experts. We have simplified the problems we have discussed considerably, ignoring many important tax rules, including but not limited to: discussions of the impact of different rates for long-term versus short-term capital gains tax, different rates at different income levels, the value of capital gains tax loss carryforwards, estate, trust and charitable considerations, and many, many more.

Further Reading and References:

- Domar, Evsey D. and Richard A. Musgrave. “Proportional Income Taxation and Risk-Taking.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics. Vol. 58, issue 3, 388-422. 1944.

- Feldstein, Martin. Capital Taxation. Harvard University Press. 1983.

- Feldstein, Martin. “The Effects of Taxation on Risk Taking.” Journal of Political Economy. Vol. 77, No. 5, 755-764. 1969.

- Haghani, Victor, Larry Hilibrand and James White. “When it Pays to Pay Capital Gains.” 2019.

- Haghani, Victor and James White. “How Much Should the Tax Tail Wag the Asset Allocation Dog?” 2017.

- Haghani, Victor and James White. “Measuring the Fabric of Felicity.” 2018.

- Haghani, Victor and James White. “To Realize, or Not to Realize: Capital Gains Tax and Portfolio Choice.” 2020.

- Stiglitz, J. E. “The Effects of Income, Wealth, and Capital Gains Taxation on Risk-Taking.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics. Volume 83, Issue 2, 263–283. 1969.

- This not is not an offer or solicitation to invest. We are not tax experts and nothing in this note should be construed as tax advice. Past returns are not indicative of future performance.

We are very grateful for the help of Larry Bernstein, Richard Dewey, Larry Hilibrand, Peter Hirsch, Mark Perwien, Jeffrey Rosenbluth and Roberta Sydney. All errors are our own.

- Based on studies by the Federal Reserve on the distribution of stock market ownership by household net worth, and also supported by average US Treasury capital gains tax receipts of roughly $100 billion per year. See here and here. This does not include further exposure of the US Treasury to US equities through corporate tax receipts, which tend to run twice the size of annual capital gains tax receipts.

- For those familiar with Utility theory, Risk-Adjusted Wealth is equivalent to Certainty-Equivalent Wealth.

- For example, see Domar and Musgrave (1944), Stiglitz (1969) and Feldstein (1969). Also assuming zero risk-free interest rates, that the capital asset has a zero dividend rate (which can be achieved for equity risk by using equity index futures), and that the investor is willing and able to borrow to leverage her position in the capital asset, if required, at the risk-free rate.

- There are proposals to start taxing unrealized gains too. We’ll leave discussion of that for a future note, if it becomes more likely. Also, under current rules, taxpayers can allocate $3,000 of capital losses per year to offset earned income.

- This could result, for example, from a view that equities have a 4.5% expected excess return and 18% risk, both per annum, and the investor’s preferences are represented by a CRRA utility function with coefficient of risk-aversion equal to 2. See our note Measuring the Fabric of Felicity for the risk-aversion survey supporting this Base Case choice.

- For example, by donating the assets to a charity or having children inherit the assets and utilize the step-up basis allowance.

- It should be noted this is an odd sort of option contract, whereby the seller determines the expiration date of the option and under current rules the option goes away at death.

- A parameter that we have built into the accompanying calculator.

- The 81% is measured on the basis of $100 of portfolio value, ignoring the capital gains tax liability. If instead we value the starting portfolio at $89.50, net of the current value of the tax liability, then the desired allocation to equities is 90.5%, much closer to the 98.5% allocation that we’d get if capital gains taxation were applied symmetrically.

For a case of the risky asset having a zero basis, we find an optimal equity allocation of 85%, which scales up to 115% as a percentage of starting wealth minus current value of the tax liability, a result higher than the 98.5% optimal under symmetric taxation.

- We assume that stock and bond prices do not fall when inflation rises. The impact of higher inflation on Risk-Adjusted Wealth in this scenario flows through the fact that investors are taxed on nominal income, not income after inflation.

- In the Base Case, equities are expected to grow at 4% a year (6% total return less 2% dividend yield) so after 20 years $76 invested in equities would be expected to grow to $169 for a capital gain of $93 and at 20% tax, an extra $18.60 of tax, compared to about $5.70 of wealth tax payable over the period.

Previous

Previous