February 5, 2025

Featured Insights

Out of the Frying Pan and Into the Fire: Selling A Highly Appreciated Stock Without Paying Taxes?

By Victor Haghani and James White1

ESTIMATED READING TIME: 5 min.

Over the past 20 years, more than a few investors have made huge returns through concentrated holdings in a few remarkable companies. Twelve of the twenty largest S&P 500 companies have increased in value more than 10-fold over that period, with a handful growing more than 100-fold, not to mention the gains on Bitcoin and other digital currencies. Then there are the fabulous venture capital success stories, where early-round investors have made 1,000-fold returns or more. One notable case is Jeff Yass and his partners at Susquehanna, who may have made close to a 10,000-fold return on a $5 million investment in TikTok owner Bytedance.2

It is natural that many, if not most, of these happy investors would like to take some chips off the table and diversify their portfolios – and, if possible, they’d like to do it tax-efficiently too.

“I work for a private bank, and I’m here to help”

Of course, wealth managers have come up with ways to help. In this note, we’d like to share our analysis of one potential solution we’ve been hearing about a lot lately. It involves leveraged direct index tax loss harvesting. It promises to transition an appreciated single stock holding into a diversified portfolio like the S&P 500 in about ten years, without realizing any capital gains along the way.

It sounded a little too good to be true to us, and that’s pretty much what our analysis concluded. We should emphasize that we have not had any discussions with purveyors of this strategy, so we’re just going on what some of our clients have told us and it’s possible that we have misunderstood the strategies that are being suggested to attain this tax Nirvana. We recognize there are particular tax circumstances where these leveraged strategies can make sense,3 but here, we’re focused on the case of a US investor selling a highly appreciated asset with long-term gains, buying a diversified equity portfolio and avoiding long-term capital gains in the transition.

Out of the frying pan…

Let’s assume your whole portfolio consists of $10 million in one stock – say, Apple – with a cost basis of just 1% of its value. You want to sell it, and diversify your portfolio by investing the proceeds, after tax, into the S&P 500. Your wealth manager suggests that you enter into a managed strategy which buys $10 million of individual stocks and simultaneously shorts $10 million of other stocks. The longs and shorts will be run following a quantitative strategy that they suggest should generate a risk-adjusted profit – or, in the parlance of stock picking, generate alpha. Instead of just buying and shorting the S&P 500, this “alpha” component is important, because for the strategy to generate the promised tax benefits, US tax rules require that the strategy exposes your capital to a risk of loss.

The way the strategy generates capital losses is that the manager will sell long positions that go down, and buy back short positions that have gone up. As this long-short portfolio of individual stocks generates capital losses each year, you sell an amount of your Apple that will generate an equal capital gain, and use the proceeds to buy more of the portfolio of individual stocks you already own.4 It’s likely the case that by the end of 10 years (or sooner) you could have sold all your Apple without realizing any net capital gains. Assuming a 6% annual growth rate of the stock market, after 10 years, you’d expect to have a portfolio of about $36 million of single stock long positions against about $18 million of single stock short positions.

…and into the fire

Assuming an annual fee for managing this program of 0.7% and a long-short financing friction of 0.6% per annum, you’d have paid out an after-tax $1.8 million in total over the ten years, or about 10% of your ending wealth. That’s about one-half to three-quarters of the total tax you’d have paid – depending on your capital gains tax rate – if you’d just sold your Apple position to begin with.

It appears to us that to preserve the core tax benefits, an investor using this leveraged harvesting approach will be stuck in the program indefinitely – paying fees and financing frictions on a portfolio with diminishing tax loss harvesting opportunities, and exposure to a fair amount of tracking risk versus a well-diversified index. The reason is that if, after all the Apple has been sold, you decide to close out the $18mm x $18mm long versus short positions, you’d realize much of the capital gains that you were trying to avoid. We estimate that after around 20 years in this program, the fees and frictions would exceed the taxes you were trying to save, and you’d still have a huge unrealized tax liability embedded in your portfolio. You’d be worse off than if you’d just sold your Apple stock at the beginning and put the proceeds, net of capital gains tax, into the portfolio you wanted.

What about alpha?

Implicit in our analysis is the assumption that you don’t expect the stock-picking strategy behind the long and short legs of the leveraged direct-indexing to generate alpha. We think that’s a reasonable premise: if the tax benefits hadn’t been pitched, you likely would have been skeptical of this strategy in the first place.

We advise caution in the presence of the “tax-avoidance distortion field,” which can trick you into believing in an investment strategy you’d otherwise ignore just to justify the tax perks. Psychologists call this “cognitive dissonance avoidance.” For example, after you vote for a politician whose character you initially disapproved of but whose tax policy you liked, you then change your mind and no longer disapprove of his character.

Of course, you’ll be shown a historical back-test that suggests the chosen stock-picking strategy beats the market, but there’s a good reason it will be accompanied by the statement “past returns are not indicative of future returns.” It’s challenging enough to beat the market without any major constraints – but with this type of strategy, the long-short portfolio becomes significantly constrained over time in that there will be many stock holdings that cannot be traded without realizing large capital gains. It’s reasonable to be skeptical that such a program can generate outperformance with one hand tied behind its back.

What about step-up basis at death?

As we stated above, over a 10-year horizon, the fees and frictions for this type of program can add up to about 10% of wealth in the program. Even if you believe that the tax rules concerning step-up of basis upon death will remain as they are today, there is still the problem that the program continues to incur fees and frictions each year beyond the full transition out of the appreciated asset. If you expect to benefit from the step-up in 10 to 20 years, then there could be a net benefit to the program – but if it’s longer than 20 years, the costs will likely overwhelm the tax savings.5 In any case, we’ll describe below that we think there’s a better approach: one which delivers less gross tax savings but not necessarily less value, is much simpler, involves less risk, and costs very little.

A closer look at the value of step-up in basis at death

Say you are 50 years old and own $100 of AAPL stock with a basis of $1, and you want to find a way to use the step-up basis rule at death so you never pay those capital gains. You find a way – for example, using a leveraged long-short direct index tax loss harvesting program – to convert your holding in AAPL into a diversified stock portfolio without paying any tax. Assume that over the next 35 years – taking you to your expected lifespan of 85 – the share price appreciation of your portfolio (net of dividends) is 5% per year, less the fees involved in running that portfolio. If the step-up basis rules are still in effect in 35 years, you’ll pay no tax on death, and experience a 5% after-tax growth rate, less fees.

Alternatively: let’s say you sell your AAPL today and reinvest the proceeds, after paying capital gains tax today, into a diversified portfolio of stocks. We’ll also assume this portfolio grows at 5% net of dividends, though with effectively zero fees. Let’s say your long-term capital gains rate is the federal rate of 24%. You’ll enjoy an after-tax rate of return of 4.35%, only 0.65% lower than the 5% no-tax return.6

There are three advantages to paying tax today rather than trying to avoid tax completely by relying on step-up basis on death:

- you avoid the fees involved in making and maintaining the tax-free transition from AAPL to a diversified portfolio, which alone could easily exceed the 0.65% after-tax return difference,

- you have eliminated the tax liability, immunizing yourself to a change in the step-up rules, or other tax changes,7 and,

- you should expect a higher risk-adjusted return from the ability to manage your fresh portfolio the way you want to, rather than being in a tax-constrained portfolio.

Of course, the numbers will be different with different assumptions about horizon, tax rates and rates of return, as well as your assessment of the risk of tax law change and other factors – but we hope this example illustrates that it won’t always make sense to defer or avoid taxes at the cost of fees, complexity and constraints.

Keeping it simple: don’t let the tax tail wag the investment dog

An alternative approach that we wrote about recently in “Direct Indexed Tax Loss Harvesting: Is the Juice Worth the Squeeze?” is to keep it as simple as possible – no leverage, no shorts, no individual stocks. Just incrementally sell the appreciated asset: a lot at first and then less over time, and replace it with low-cost ETFs that give you exactly the diversified portfolio you want, doing tax-loss harvesting on your ETF portfolio during the transition.

Selling a good chunk of Apple in the first few years and using the proceeds to buy ETFs which you will then manage tax-efficiently will give you expected savings of about one-third of the total starting capital gains tax liability, as you can see in the spreadsheet in the Appendix.8 It will save you 100% of the fees, frictions, additional risk and complexity involved in trying to pay no tax at all. Also, importantly, you’ll benefit from reducing your risk to your appreciated single stock position more quickly. After just a few years, you’ll have almost fully migrated to the diversified portfolio you want, and you’ll have less unrealized capital gains than in the leveraged long-short direct index program, because you already paid a good portion of them.

There may be particular circumstances where a more complex approach is warranted, but for most people in most cases, a simpler, quicker and more cost effective approach that pays some tax as part of the de-risking process is preferable to solutions that keep you locked in, paying fees and frictions for decades, and involve leverage, shorting and hundreds of individual stock positions.

Appendix: Optimizing the transition from an appreciated single stock holding to an ETF portfolio

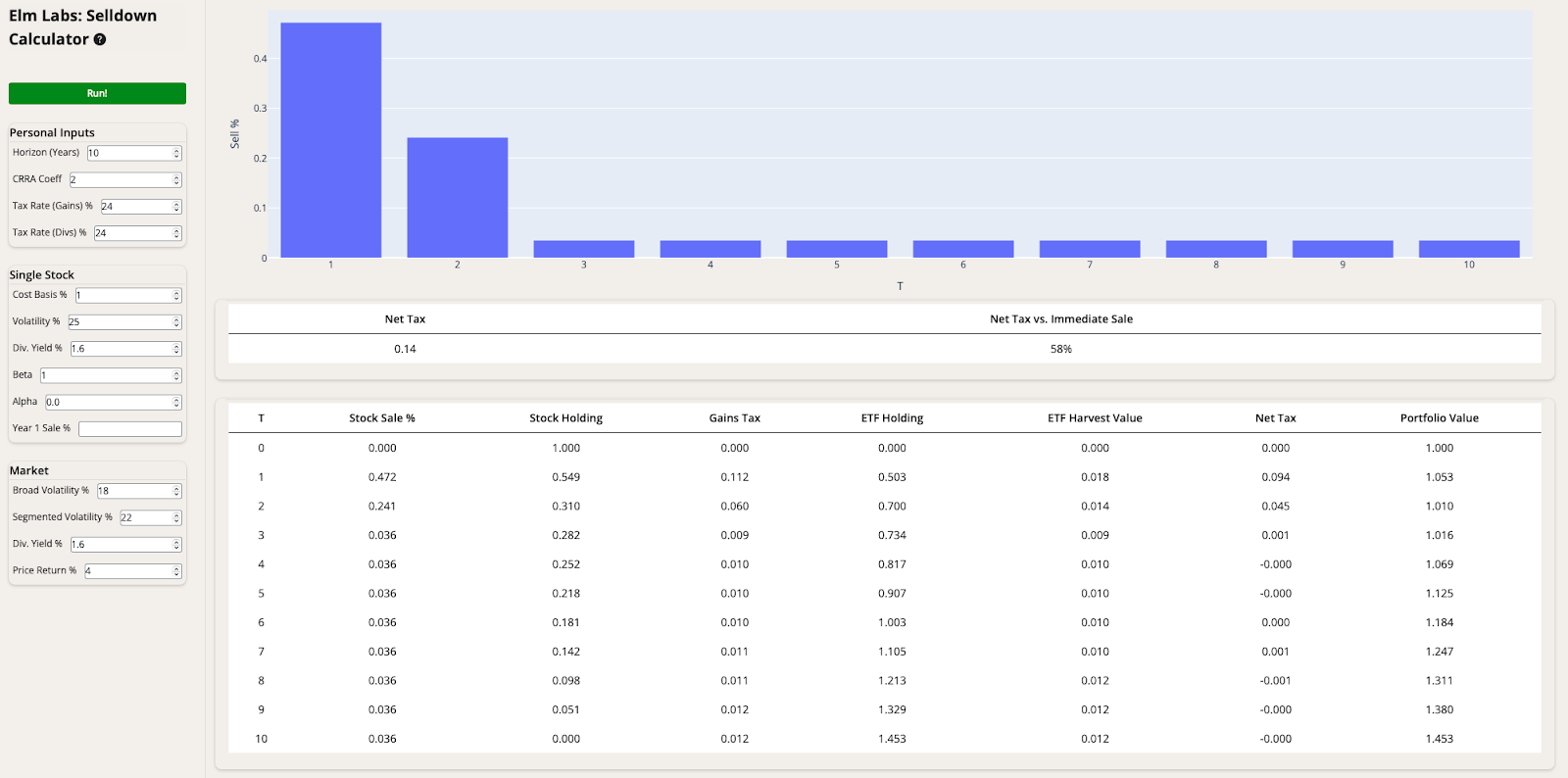

We have recently built a tool that generates the output below, with a schedule for selling an appreciated single stock holding and replacing it with a portfolio of diversified ETFs over time. Feel free to give it a try here or get in touch with us to discuss using the calculator for your particular situation.

Here’s how it works: this tool calculates the selldown schedule for an appreciated asset which robustly maximizes the horizon certain-equivalent return (CER) of the portfolio given the input asset dynamics and coefficient of risk aversion (CRRA Coeff).

We assume that a fraction of the appreciated asset is sold on the first day of each year, the cash is invested in a segmented-ETF program which engages in tax loss harvesting, and taxes on the realized gains are paid in the following year.

We use the value of lookback options to estimate the value of the segmented-ETF tax loss harvesting, and haircut the theoretical value by 5%. We also include a small smoothness penalty in the objective function which tends to produce a slightly more prolonged selldown schedule, and causes the results to not be exactly CER-optimal – however, we believe this produces results which are more robust and only very slightly sub-optimal.

Further Reading & References

- Haghani, V. (2015). “Infographic: How much do taxes matter in investing?” Elm Wealth.

- Haghani, V. and White, J. (2017). “How Much Should the Tax Tail Wag the Asset Allocation Dog?” Elm Wealth.

- Haghani, V. and White, J. (2018). “US Tax Reform Leaves Even Less of the Pie for Individual Investors in Alternatives.” Elm Wealth.

- Haghani, V., Hilibrand, L. and White, J. (2019). “When it Pays to Pay Capital Gains.” Elm Wealth.

- Haghani, V. and White, J. (2020). “To Realize, or Not to Realize.” Elm Wealth.

- Haghani, V. and White, J. (2023). “Chapter 17: Tax Matters.” The Missing Billionaires: A Guide to Better Financial Decisions. Wiley.

- Haghani, V. and White, J. (2024). “Direct Indexed Tax Loss Harvesting: Is the Juice Worth the Squeeze?” Elm Wealth.

- Liberman, J., Sialm C., Sosner, N. and Wang, L. (2020). “The Tax Benefits of Separating Alpha from Beta.” Financial Analysts Journal 76:1.

- Moehle, N., Kochenderfer, M., Boyd, S., and Ang, A. (2021). “Tax-Aware Portfolio Construction via Convex Optimization.” BlackRock AI Labs.

- Sialm, C. and Sosner, N. (2018). “Taxes, Shorting, and Active Management.” Financial Analysts Journal 74:1.

- Quantitative Investment Strategies. (Feb 2018). “The Benefits of Tax Loss Harvesting Strategies in Investment Portfolios.” Goldman Sachs Asset Management.

- This is not an offer or solicitation to invest, nor are we tax experts and nothing herein should be construed as tax advice. Past returns are not indicative of future performance. Thanks to Dave Blob, Larry Hilibrand, Chi-fu Huang and Jeffrey Rosenbluth for their input, and special thanks to Vlad Ragulin for his contributions, and to our colleagues Jerry Bell and Steven Schneider for their help.

- That’s about $50 billion, in case you were wondering but didn’t feel like dealing with all those zeroes.

- Such as for people who are imminently moving from high tax to low tax states, or who are confident they’ll get a step-up in basis at death in just over 10 years, or for investors who would value a strategy that generates short-term capital losses offset by long-term capital gains.

- Or you could also just buy an S&P 500 index ETF, but you’d miss out on more tax-loss harvesting by doing that.

- If you expect to get step-up basis in just a few years, perhaps just holding the appreciated asset may be the most attractive option.

- You might have expected the after-tax rate of return would be 3.8% = (1 – 24%) * 5%, but it’s 4.35% because as your horizon gets longer, a smaller difference in compound returns is needed to make up for the fixed dollars of taxes paid at the start.

- Also, if you care about inequality or if you think of paying taxes as having some philanthropic impact, you may prefer paying a given amount of taxes than paying the same amount in fees to an investment manager to avoid paying taxes.

- This expectation depends mostly on assumptions of volatility of the assets involved, and it’s important to realize it’s an expectation – the actual realized losses from the ETF portfolio will depend on the path taken by market prices over the period, though some of that variation can be hedged.

Previous

Previous