July 14, 2021

Risk and Return

Are Market Capitalization Weighted Indexes Too Concentrated in the Biggest Stocks?

By Victor Haghani and James White 1

Apple and Microsoft each represent over 5% of the S&P500, with Amazon and Google not far behind. The ten largest US companies add up to 27% of the S&P500. Historically, the top ten companies have represented a smaller fraction of the S&P500; for example, from 2005 to 2019 the average was about 20%. We’re often asked if this unusually high concentration at the top is something to worry about. For investors like us who believe the markets are pretty efficient, we think the answer is “no” on three counts:

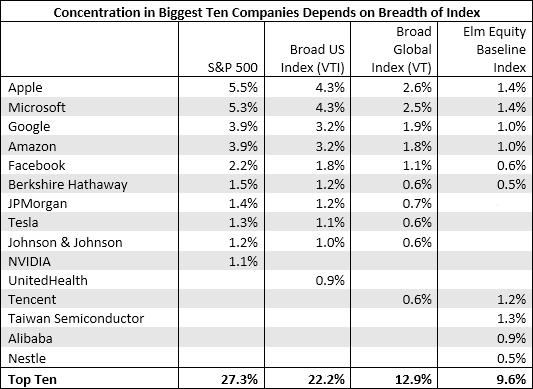

- First, the broad stock market isn’t as concentrated as the S&P500 suggests. The S&P500 covers about 80% of the total US stock market, and less than 50% of the global stock market by value. Indeed, the S&P500 owns less than 6% of all the public companies that a broad, global equity fund such as Vanguard’s VT owns. So a globally diversified portfolio of stocks is roughly half as concentrated as the S&P500, with about 13% in the top ten companies, and Elm’s global equity Baseline is even less concentrated with about 10% in the top ten names,2 as shown in the table below. Vanguard’s global market capitalization weighted index fund is invested in over 9,000 individual companies, and the 1,000 largest holdings comprise only 75% of the total index. We think few investors would view this as a portfolio low on diversification, but we’ll expand on this perspective further in the two points below.

- Let’s consider an alternative to a market capitalization weighted index that invests the same dollar amount in every stock in the index – referred to as an equal-weight index.3 Every investor who allocates to the equal-weight index has to find someone else who is willing to hold even more of the largest stocks and go short the smaller stocks, to in effect take the other side of the active bet that the equal-weight investor is making. Getting someone to take the other side of your trade may well require you to accept a lower return. Taken to the extreme, if all the capital invested in market capitalization index funds wanted to switch to equal-weight index funds, they’d either have to own substantially more than 100% of many of the smaller companies – assuming their prices didn’t change – or they’d wind up forcing all companies to have market capitalizations closer to each other, regardless of the underlying characteristics of their businesses. No wonder the largest equal weight S&P500 index fund (RSP) is only 2% of the size of the largest market capitalization weighted US equity index fund (VTI).

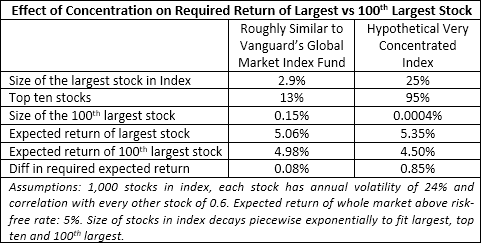

- The market capitalization weighted portfolio is the only portfolio that all investors can own at the same time. For investors to be happy holding more of the biggest names, they need to deliver just enough extra expected return to compensate for their being such a big part of the market.4 How big an assumption this is depends on how concentrated the market is in the biggest companies. The table below gives an estimate for the amount of extra expected return that the largest stocks would need depending on how dominant they are in the index.

Notice that, with a size distribution similar to that of today’s global stock market, the largest stock would only need to deliver a tiny bit more expected return (0.08%) than the 100th largest stock for the market capitalization weighted portfolio to be the most efficient portfolio. In other words, this result is telling us that the current market portfolio, with the top ten stocks representing about 13% of the market, isn’t very concentrated at all. By contrast, if we assumed that the largest stock represented 25% of the market portfolio (a truly extreme degree of concentration), then that stock would need to have a significantly higher expected return to compensate for its outsized impact on the overall market.

Notice that, with a size distribution similar to that of today’s global stock market, the largest stock would only need to deliver a tiny bit more expected return (0.08%) than the 100th largest stock for the market capitalization weighted portfolio to be the most efficient portfolio. In other words, this result is telling us that the current market portfolio, with the top ten stocks representing about 13% of the market, isn’t very concentrated at all. By contrast, if we assumed that the largest stock represented 25% of the market portfolio (a truly extreme degree of concentration), then that stock would need to have a significantly higher expected return to compensate for its outsized impact on the overall market.

In this stylized analysis, we assume that every stock’s idiosynchratic (non-market) risk is independent of that risk in every other stock. In reality, we know that groups of stocks can share common traits, such as the industry they’re in, or other characteristics, often referred to as “factors,” such as size, growth prospects, etc. An equal weight index will always have a bias in favor of small companies versus large ones, and in general will also have a bias to value stocks over growth stocks. These risks can lead to substantial divergences in performance between market capitalization and equal weight indexes, with differences in one-year returns of more than 5% occurring 25% of the time.

Conclusion

While market capitalization weighted indexes are currently more concentrated than usual, they are still very well diversified based on the small amount of extra expected return the biggest stocks would need to offer to compensate for their weight in the index. In sum, market capitalization weighting is the best index design available, offering the most efficient and diversified exposure to the broad stock market.

- This not is not an offer or solicitation to invest, nor should this be construed in any way as tax advice. Past returns are not indicative of future performance.

- The concentration figures for Elm’s global equity Baseline are calculated for our Global Balanced strategy for US SMA investors. Figures will vary slightly for our other programs.

- Another alternative to market capitalization weight indexing we could have considered is referred to as “Fundamental Indexing.” We believe the analysis presented here also applies to this form of indexing. See our article published in the Journal of Portfolio Management titled “Do Index Buyers Make Over-Valued Stocks More Over-Valued?” which argues against the proposition of Fundamental Indexers that market capitalization weighted indexing is flawed.

- Indeed, this is a central tenet of Portfolio Theory.

Previous

Previous