January 2022 Investor Call Q&A with Victor & James

By Victor Haghani and James White

Thank you to all our investors who participated in our first Investor Call. Feedback has been very positive, and we look forward to doing it again. If you’d like to watch or listen to the full recordings, you can find them here:

Elm Investor Calls

Due to time constraints, we weren’t able to answer every question that came up during our discussion, so we wanted to take the opportunity to answer a few which we thought would be of general interest:

Why do non-US return expectations remain similar despite a decade of under-performance, and should allocations go up or go down given that under-performance?

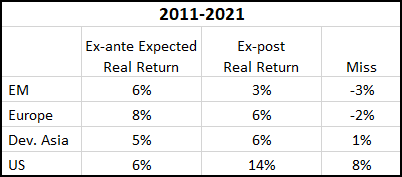

Here’s the picture of real return expectations from 10 years ago vs actual real returns:

Over this period, two major markets under-performed our expectations and two out-performed. Looking at it another way, non-US markets in aggregate had historically normal, solid levels of real returns, and US returns were virtually unprecedentedly positive from a historical perspective.

A difference of 2-3% vs. expectations over 10 years is very normal (the standard deviation of 10-year real returns is 5% to 6% per annum), so the major surprise is not the modest levels of performance difference relative to expectations from non-US markets, but rather the dramatic out-performance of the US market versus expectations, at a level which virtually no-one would have rationally forecast back in 2011, nor which (we think) could be rationally forecast for the next 10 years.

Given these results, the message seems to not be “something really went wrong in non-US markets that now needs to be accounted for,” but rather that the US simply had an idiosyncratic period of incredible performance. Most individual markets see occasional periods of both dramatic, unexpected out-performance and under-performance, and this is one of the reasons we favor a portfolio which is internationally diversified. So, the performance picture over this period does not especially make us question our general methodology for non-US markets.

Separately, we believe that, while a decade feels like a long period of time to us humans, for assets like equities with long-term historical and expected Sharpe ratios of around 0.3, 10 years is simply too short a period from which to draw strong quantitative conclusions, as we discuss in this note: What’s Past is Not Prologue.

Does Elm currency-hedge international investments?

All non-US equities are owned in their local currencies. Please see our FAQ #20 for a discussion of our reasons for this.

Is the severe negative real-yield environment driving investors to make riskier investment decisions?

We certainly think so. In our view, both quantitatively and intuitively, the negative level of real-yields across the maturity spectrum is heavily responsible for much of the market dynamics of the last several years.

At Elm, the connection between real yields and risk is algorithmic: all other things equal, as real yields fall we see the excess real return of equities rise, which generally means we want to own more equities in that environment.

The market overall is certainly not acting as systematically, but we think the general logic is the same: if you’re choosing between bonds and equities, and bonds are priced at a prohibitively unattractive level, then all else equal equities and other equity-like assets are going to look very attractive.

With regards to your use of TIPS in calculating excess equity returns, how sensitive is your allocation to the 10-year point? What about the 2-year, 5-year, etc.?

At Elm, we only use 10-year TIPS for our measure of the long-term risk-free rate. This is not perfectly ideal, but in practice we do it for three main reasons:

- Equities are a long-duration asset, and we’re trying to forecast long-term returns, so we want to use a long-term rate

- The 10 year point is the reference long-term point on the TIPS curve. 30 year TIPS are much less liquid and have not been issued consistently

- We want to keep things simple

Will short positions or options positions ever be part of the portfolio?

We don’t expect so. With respect to short positions, we (Victor and James) both have the vast majority of our wealth invested in Elm strategies, many of our clients do as well, and we want Elm strategies to be appropriate for handling large fractions of a client’s wealth. In our view that rules out leverage and shorting, aside from the variety of other issues that can be present with leverage, one of which we discuss in this fun note: George Costanza At It Again: The Leveraged ETF Episode.

With respect to options positions, we’ve recently written a note about options for the Journal of Derivatives which we hope to share with clients shortly as well. One of our conclusions is that options are primarily useful for investors who aren’t able or willing to dynamically rebalance their portfolio. Elm of course is dynamically rebalanced, so we don’t see much fit for options in our strategies.

What are things that could happen which your approach to wealth-management is not prepared for?

All of the below events would require us to rethink or change aspects of our approach. We think all are extremely unlikely:

- ETFs decouple significantly from their underlying investments, or become significantly illiquid

- The US Treasury discontinues issuing inflation-indexed bonds

- Major markets impose regulatory constraints to US entities owning their domestic equities

- Equity and/or ETF trading costs increase significantly

Thank you again to all those who participated in the call and this conversation! We’re already looking forward to our next investor call.

Interested in more like this?

Subscribe to our mailing list and get notified about new Elm news and research.