August 27, 2024

Taxes

Direct Indexed Tax Loss Harvesting: Is the Juice Worth the Squeeze?

By Victor Haghani and James White 1

Estimated reading time: 6 min.

The content on this page is being provided as general market commentary and for educational purposes only. It does not constitute any form of investment advice, or any form of recommendation to buy or sell any securities or adopt any investment strategy mentioned herein, or any form of advertisement for Elm Wealth services or strategies. Any investment strategies and investment results discussed herein are for illustration purposes only in the context of the commentary, and do not reflect actual or hypothetical Elm Wealth strategies or results, or an offer to provide such strategies or results. This content is intended only to provide observations and views of the author(s) at the time of writing, both of which are subject to change at any time without prior notice. The information contained in the commentaries is derived from sources deemed by Elm Wealth to be reliable but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. This material does not have regard to specific investment objectives, financial situation and the particular needs of any specific reader. Any views regarding future prospects may or may not be realized. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Introduction

Most people have come to agree that investing in low cost, diversified index funds is a good idea. Most people also like paying less in taxes and deferring their payment into the future.2 Direct Indexed Tax Loss Harvesting (DI) programs combine these benefits into one package. And wealth managers like them too, as they can charge extra fees by putting their clients into DI programs rather than steering them into index funds offered by Vanguard or Blackrock. Investors have been so convinced of the benefits of DI that Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and JPMorgan manage upward of $300 billion in these programs.3

In this note, we’re going to throw some cold water on the DI love-fest by explaining why most tax-sensitive investors would be better off with a simpler approach to tax loss harvesting.4 We call this approach Segmented ETF investing, and it involves building your desired portfolio using low-cost sector and (optionally) international ETFs. Segmented ETF investing is expected to generate a similar amount of tax losses as Direct Indexing, but without DI’s costs, risks and limits on diversification. The main problems of Direct Indexing stem from the difficulties of attempting to harvest single-name losses, while tightly tracking a benchmark index and complying with the Wash Sale rule.

How does Direct Indexed Tax Loss Harvesting work?

Most DI programs involve a separately managed brokerage account in which the investment manager buys a portfolio of hundreds of individual US stocks, with the goal of matching an index such as the S&P 500.5 Then, the manager routinely sells any stocks below their cost basis in order to realize those capital losses.6 Once a loss is realized, 30 days must elapse before the same stock can be repurchased – the “Wash Sale” rule – so the manager must buy different stocks to replace those which were sold. In doing so, they attempt to keep the portfolio statistically matching its benchmark index as closely as possible – but it’s impossible to perfectly match the benchmark once harvesting has commenced.

How much capital losses should you expect to realize?

To evaluate DI against alternatives, we need a sense of the magnitude of losses we can expect to realize, and what it depends on.

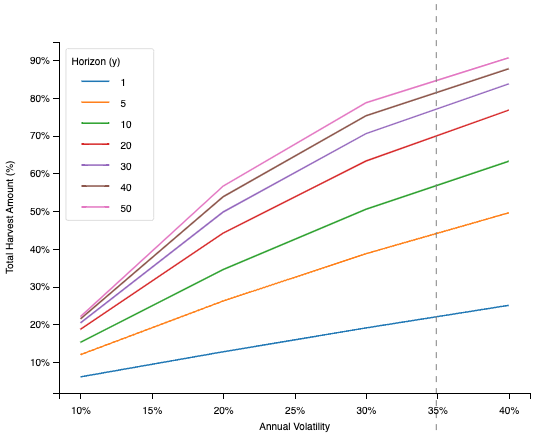

Let’s say there was no Wash Sale rule, so you can realize losses anytime they’re available without changing your portfolio composition. For each stock, the amount of losses we should expect is related to the value of a put option on the stock.7 Just as with a put option, the expected harvest will depend on the stock’s volatility, its dividend yield, the risk-free rate and the horizon. In the chart below, we show an estimate of expected harvesting over different horizons and volatility levels.8

The average volatility of individual US stocks over the past five years has been 35%, as shown on the chart above.

Notice that the amount of losses harvested is roughly proportional to the stock’s volatility. This makes it pretty clear why DI was developed: individual stocks are much more volatile than broad stock indexes. Notice also that as horizon lengthens, the amount of expected harvesting increases (as shown by how much each line rises above the line below it), but by less and less. We’ll come back to discuss the implications of these characteristics shortly.

Direct Indexing headwinds

There are three major consequences from complying with the Wash Sale rule, which together reduce the amount of harvesting expected in real-world DI programs:

- Over time, the portfolio will not match the index exactly and may earn higher or lower returns than the index. This is known as “tracking error.”

- Managers and clients are worried about too much tracking error – with reason, because it can be hard or impossible to distinguish “random” tracking error from systematic underperformance. As a result, managers generally operate under a relatively tight tracking-error constraint, which can significantly limit the amount of harvesting available.

- In the long term, some of the tracking error will be hard-baked into the portfolio, since bringing the portfolio back to the index would realize capital gains which is at odds with the tax-loss harvesting objective.

One particularly disturbing aspect of DI tracking error is that there is reason to fear it has a negative expected return. Whenever an investment strategy veers away from the market portfolio, it is engaging in a zero-sum activity requiring some other market participant to be on the other side of the trades it is doing. The trades that DI portfolios need to make are largely predictable by sophisticated market participants. While it’s not possible to know exactly who is on the other side of DI trades, we do know that there are a number of hedge funds and trading firms – Citadel, RenTec, Virtu and DE Shaw, to name just a few – that make a pretty steady and sumptuous living by being at the top of the stock-trading food chain.

With the passage of time and the general expected upward drift of the stock market, there will be fewer and fewer tax loss harvesting opportunities for the portfolio. Eventually the portfolio will have investments almost entirely with unrealized gains. This is mitigated to a small degree by the potential of investing incoming dividends, although with the 1.25% US stock market dividend yield, this doesn’t help much over typical horizons. Unfortunately, even though a “seasoned” DI portfolio may not be generating significant harvesting opportunities, it’s still a complex portfolio of hundreds of stocks which must be monitored and re-balanced, and will usually continue to be subject to DI management fees.

A better way: Segmented ETF portfolios

We believe that for most investors, Segmented ETF investing is a better way to combine the benefits of index investing with tax-loss harvesting.

Start by choosing the baseline portfolio of asset classes that is right for you.

Next, build your portfolio using the most segmented, broadest range of low-cost index ETFs to represent that baseline. For example, the broad US stock market can be segmented into eleven low-cost sector ETFs, and regional international ETFs can be used for the broad non-US stock market if desired.

Finally, realize losses in that portfolio of ETFs whenever available. The key here is that this can typically be done with considerably less tracking risk – and effort – than in Direct Indexing. This is because multiple ETFs tracking similar, but not identical, indexes are available for most asset buckets. For example, there are multiple “flavors” available in ETF form for the US Real-estate sector – they’re different enough that moving between them doesn’t trigger the Wash-Sale rule, but similar enough that switches introduce much less tracking error compared to Direct Indexing.

Recall that the expected amount of harvested losses is roughly proportional to the volatility of the assets in the portfolio. Industry sector ETFs and regional international ETFs are, on average, more volatile than the broad stock market, and have exhibited about 70% of the volatility as the average individual US stock. The table below compares realized volatility over the past five years.9

| Realized Annual Volatility | |

| US Single Stock Average | 35.1% |

| US Sector Average | 25.2% |

| S&P 500 | 21.2% |

| Intl. Region Average | 21.1% |

| Intl. Total Market | 19.6% |

To a first approximation, a TLH program using sector ETFs would deliver about 70% of the capital losses that a DI program could potentially generate – but remember that most DI programs do not deliver on their full potential, because most programs put a limit on tracking risk. From our own experience and from discussions with people who have been in popular DI programs, we believe these programs typically harvest less than 70% of their potential harvesting, were tracking risk not a concern.

In summary: you should expect roughly the same amount of loss harvesting from a portfolio of sector and regional international ETFs as can be expected from Direct Indexing with typical limits on tracking risk.

Segmented ETF investing: have your cake, and eat it too

Segmented ETF investing is superior to Direct Indexing in almost every dimension beyond the roughly equivalent expected harvesting generated by the two approaches.

- Tax-loss harvesting an ETF portfolio is usually offered for zero additional fee from most ETF portfolio managers. The weighted average expense ratio of the underlying ETFs in a segmented ETF portfolio is 0.1% or lower. This compares to fees for DI of around 0.35% for very large accounts, and in many cases more than 1%. For most investors, the effective cost of these fees is considerably higher due to IRS limits on deducting managed account fees against income. Such fees can completely eliminate the expected risk-adjusted benefit of Tax-Loss Harvesting for many investors.

- Segmented ETF investing involves much lower tracking risk and, more critically, no reason to believe that the tracking error will be negative.

- The Segmented ETF portfolio will continue to represent the desired baseline, rather than drift into an unbalanced single stock portfolio with baked-in tracking risk versus the desired index and the need for ongoing management even when the portfolio has limited opportunities for generating capital losses.

- Another advantage of the Segmented ETF approach is that it gives you the ability to choose a more diversified baseline, including exposure to international equities, rather than being limited to a portfolio of several hundred of the largest US stocks. For example, Vanguard’s eleven US industry sector ETFs give exposure to over 2,500 individual US stocks, and their international ETFs give exposure to another 10,000 stocks! Recent research has highlighted the importance of investing with the broadest diversification possible by showing that the best-performing 4% of listed companies account for the net gain for the entire US stock market since 1926.10 A DI program which invests in just 10% or less of available stocks runs the risk of missing out on some of those 4%.

There is one advantage of DI worth noting, which is that it is expected to generate a steadier stream of harvested losses than a Segmented ETF portfolio. This is because the idiosyncratic risk of individual stocks is much higher than that of industry sectors or international regions. Even if the market goes up, there will usually be quite a few individual stocks that will offer the opportunity to realize losses.

If desired, the lumpiness of the capital losses generated by a Segmented ETF approach can be offset by owning a modest extra amount of each ETF. This hedge will compensate you for having fewer losses to realize if the market goes up.

Both approaches can be customized to reflect your desire to underweight a particular sector, such as a finance industry professional wanting to avoid financial stocks. However, there are some customizations – such as wanting to only own companies with headquarters in particular US states – which Segmented ETF investing will not be able to accommodate.

Conclusion: Don’t Let the Tail Wag the Dog

We believe the all-in net benefit of Direct Indexing programs can be improved upon for many investors by instead taking advantage of Segmented ETF investing, and harvesting losses if and when they present themselves. In short, why wouldn’t you prefer an approach which delivers about the same expected amount of capital losses via a more diversified portfolio, but without the high fees, risks and complexity of investing in hundreds of individual stocks?

Investors with an abundance of short-term capital gains

For investors who tend to have a steady stream of short-term capital gains, the conventional tax-loss harvesting approach can be significantly improved upon – and in a seemingly counter-intuitive way.

Instead of trying to defer realizing a long-term gain as long as possible, it can make sense to realize the gain immediately after one year has passed since purchase and the gain becomes subject to the preferential long-term tax rate. If the asset is sold and repurchased, the basis in the asset and the “basis clock” are both reset, thereby creating the option to realize a valuable short-term loss if the asset falls in the year ahead. We call this a “clock reset” strategy.

The benefits of the Segmented ETF approach over the DI approach hold in mostly the same ways discussed above for this flavor of Tax-Loss Harvesting, too. For more details, see our research note: When it Pays to Pay Capital Gains (2019).

Further Reading and References

- Haghani, V. (2015). “Infographic: How much do taxes matter in investing?” Elm Wealth.

- Haghani, V. (2017.) “Tax-Efficient Investing for US Citizens Long-Term Resident in the UK.” Elm Wealth.

- Haghani, V. and White, J. (2017.) “How Much Should the Tax Tail Wag the Asset Allocation Dog?” Elm Wealth.

- Haghani, V. and White, J. (2018.) “US Tax Reform Leaves Even Less of the Pie for Individual Investors in Alternatives.” Elm Wealth.

- Haghani, V., Hilibrand, L. and White, J. (2019.) “When it Pays to Pay Capital Gains.” Elm Wealth.

- Haghani, V. and White, J. (2020.) “To Realize, or Not to Realize.” Elm Wealth.

- Haghani, V. and White, J. (2023.) “Chapter 17: Tax Matters.” The Missing Billionaires: A Guide to Better Financial Decisions.

- This is not an offer or solicitation to invest, nor are we tax experts. Past returns are not indicative of future performance.

Thank you to our Elm partner Jerry Bell, Larry Bernstein and Vlad Ragulin for their comments and encouragement. - However, sometimes there are good reasons to pay taxes sooner rather than later, such as if an investor expects higher tax rates in the future and/or wants to reduce tax rate risk.

- “The Direct Indexing Landscape,” March 2023, Morningstar. More than $260 billion at the end of 2022.

- We recognize there are some special situations where DI may make sense, and we’re also limiting our discussion to long-only programs that do not use leverage and shorting.

- Some DI programs do allow a modicum of international diversification but implemented using ADRs which add another layer of costs and don’t exist for many foreign stocks.

- Either to offset same-period gains, or carry forward the losses to offset future gains.

- The right to sell the stock at a pre-agreed strike price at an agreed future option expiration date. In fact, the value of harvest to a given horizon is well-represented by what is called a lookback put option, where the payoff is a function of the lowest price the stock hit over the horizon.

- Assuming weekly harvesting of one stock to the horizon, 4% risk-free rate, and 2% dividends. We recognize that it’s actually the expected value of harvesting, not the expected quantity, which is directly related to the value of put options, and not dependent on the stock’s expected return, but we’ve somewhat elided this distinction in the interest of readability.

- Assuming weekly harvesting of one stock to the horizon, 4% risk-free rate, and 2% dividends. We recognize that it’s actually the expected value of harvesting, not the expected quantity – which is directly related to the value of put options, and not dependent on the stock’s expected return – but we’ve somewhat elided this distinction in the interest of readability.

- Bessembinder, H. (2020). “Wealth Creation in the U.S. Public Stock Markets 1926 to 2019.” SSRN.

Previous

Previous