January 14, 2019

Investment Theory

If George Costanza Were a Hedge Fund Manager

By Victor Haghani and James White 1

It’s only a small over-simplification to say that investing is about predicting how things will turn out in the future, and placing your bets accordingly.2 If your prediction is right, you generally expect your bets to make money and you are happy. But there are some relatively common types of investing strategies in which your predictions about future price moves can be correct, but you lose money anyway.

Here’s an example: let’s say at the start of 2007 you have $100 of capital, and you use it to put on a trade of long $100 of Goldman Sachs (GS) and short $100 of Morgan Stanley (MS). You do this because you expect GS to outperform MS. Each month, you re-balance your trade so that both the long and short leg are equal to your current total capital, which has grown or shrunk from $100 based on the relative moves of the stocks. Rebalancing like this is not the only way to hold a long-short position, but it’s rightly popular as it significantly reduces the chance of losing more than 100% of your starting capital.

So, how did you do? The total return of GS to the end of 2018 is a loss of 3%, but MS is down 29%. You were right, GS outperformed. You made a good prediction of the future. But how much money did you make? Maybe a profit of $26, arising from the 26% by which GS outperformed MS?

Unfortunately, a $26 profit isn’t the right answer. It’s not even close. The actual outcome is you’d have lost $24! 3 Before trying to explain, we want to tell you that there’s nothing unusual about these two stocks and the paths they took.4 The crux of the explanation is that being short a stock is not the opposite of being long it. Imagine you open a brokerage account and put in $100 which you use to buy a stock. This is going to sound really obvious, but at all points in time in the future, the current value of your brokerage account will be equal to the current value of the stock. Let’s compare that with being short a stock: you again open a brokerage account, put in $100, and go short $100 of stock. If the stock goes up by 10%, now the value of your brokerage account is $90, as you have an unrealized loss of $10 on your short, but the value of your stock short is $110. Not good, and it’s not advisable to simply do nothing. If you don’t cover at least $20 of your short to bring it in line with your capital, you can find yourself running a heightened risk that you could lose your full $100 and the broker will cover your short for you.5

Keeping our focus on the short stock trade, let’s assume you initially shorted the stock at a price of $100, and then the price goes up or down each month by $10, fluctuating around $100, and at the end of the year, it’s right back to $100 where it started. Here’s where there is a big difference between being long that stock or short it. If you were long the stock, the value of your account would be the $100 you started with. But if you were short, and if your policy is to equalize the value of your short position to the value of your account once a month, you’d lose about 1% per month from rebalancing that short position.6 It’s tough to make money being short a stock: you don’t just need to be right, you need to be very right!7

Now here’s where things get even more interesting, and where George Costanza makes his appearance. If you were long GS and short MS, we’ve seen that you lost money. But what if you had the GS-MS trade the other way around, long MS and short GS? You’d lose even more money, 34% of your starting capital to be precise! What kind of devilish trading strategy loses money both ways around? Well, it’s the kind of trade that George Costanza would probably have chosen, if the producers of Seinfeld had him working for a NY hedge fund instead of the NY Yankees.

It always hurts to lose money, but it really stings when it happens despite our investment thesis proving correct, as in the case of the GS versus MS trade we started off with. In the Seinfeld episode titled “The Opposite” George complains to Jerry that every decision that he has ever made has been wrong, and that his life is the exact opposite of what it should be. Jerry, who clearly is unaware of the nature of long-short trades, tells George “if every instinct you have is wrong, then the opposite would have to be right.” Wouldn’t it have been just perfect if George, true to character, proved Jerry wrong by finding an investment that would lose money both ways around? That’s why we’re pretty sure that if George Costanza were a hedge fund manager, long-short would be his trade.

Appendix I: A More Formal Treatment

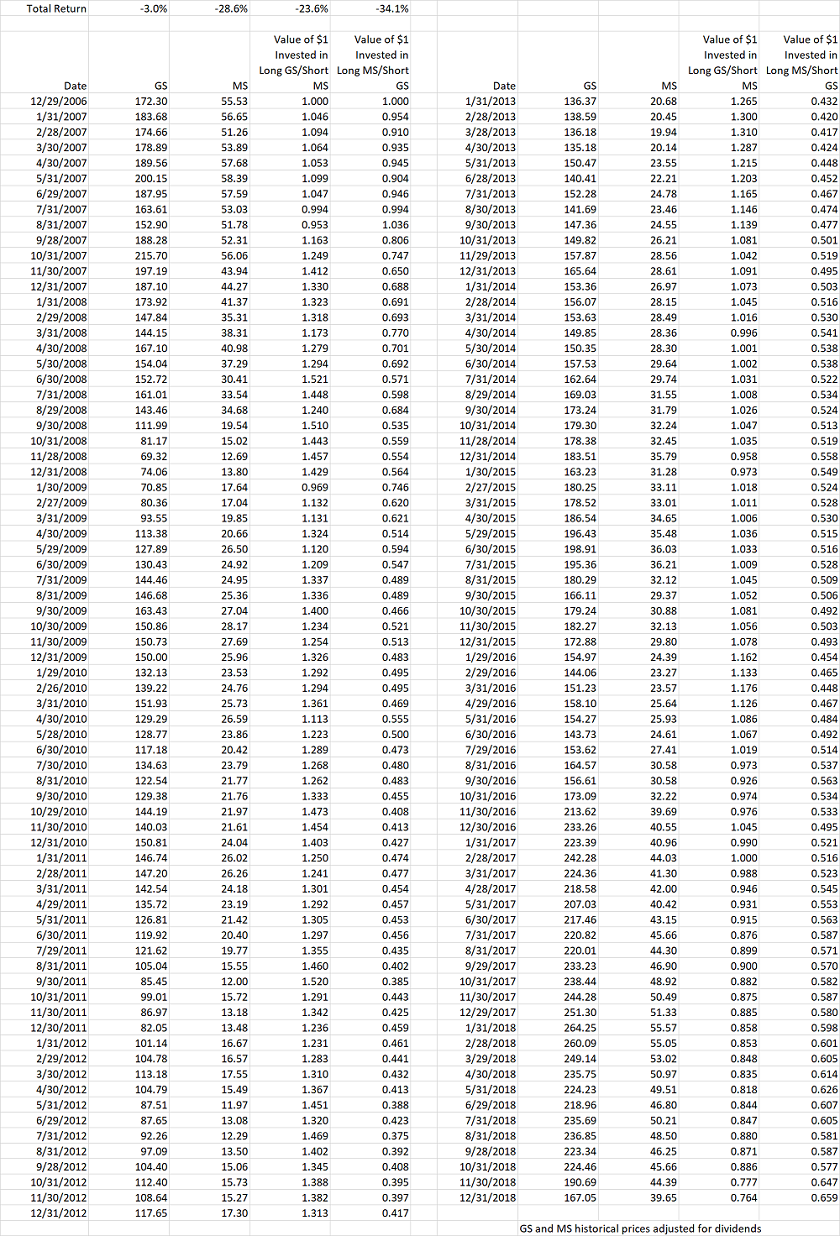

Appendix II: Historical Price Series of GS and MS, and Calculation of Long-Short Strategy Returns with Monthly Rebalancing (data from Yahoo Finance)

- Victor is the Founder and CIO of Elm Partners, and James is Elm’s CEO. Past returns are not indicative of future performance. This not is not an offer or solicitation to invest.

Thank you to Jeff Rosenbluth, Chi-fu Huang, Larry Hilibrand, Andy Morton, Vlad Ragulin, Vladimir Piterbarg, Derek Smith, and Garth Friesen for their thoughtful help with this note.

- We are devotees of thinking about investing in terms of probability distributions, scaling functions, and risk-adjusted returns, but for this note we’ll put that aside for simplicity.

- Ignoring transactions costs, borrow fees, and interest earned on your capital.

- You’d get these same results if we simulated a random walk for stocks A and B, such that one was down 3% and one down 29% over the horizon, and they had annual standard deviations of returns of 31% and 37%, and a correlation of 0.75 as GS and MS did over the period. We also confirmed this result more generally in the pool of the roughly 400 stocks that were continuously in the S&P500 from 2007 to through 2018.

- The situation with levered longs is essentially identical. The similarities between holding a short and holding a levered long position run deep.

- And all that rebalancing generates a lot of turnover, which often involves other costs and frictions. For example, in our illustrative GS versus MS trade, turnover averaged $245 per year on a starting trade size of $100.

- We hope someone will pass this note along to Elon Musk, to help him find some sympathy for Tesla short-sellers, or at least to help him feel better to know how poorly many Tesla short-sellers have been doing given Tesla’s (and Musk’s) high (44%) volatility. Even if you shorted $1mm of Tesla stock at its all-time high price of $385 per share on September 18, 2017, by the end of 2018 you’d have lost 10% of your capital, even though the stock finished the year trading at $333, down 13.5% from that all time high. See the third bullet point in Appendix I for an explanation of this 23.5% difference.

Previous

Previous