October 20, 2021

Investment Theory

Golf Guru Scott Fawcett Will Make You a Better Golfer, and a Better Investor Too

By James White, Mark Haghani and Victor Haghani 1

Introduction

Scott Fawcett’s “Decade” system of golf decision-making is revolutionizing golf strategy, and we think Scott’s approach to golf has a lot of lessons for good investing too. You may have read about him in this Golf Digest piece, or heard him on Larry Bernstein’s What Happens Next show, or the Wharton Moneyball sports analytics podcast. He’s the golf guru that US Open winner Bryson DeChambeau credits with much of his success, as does 2021 rookie of the year favorite Will Zalatoris, who Scott caddied and coached to multiple amateur titles. Scott’s approach to golf is viewed as so valuable that the NCAA forbids university golf teams to invite Scott to give team seminars, because they feel it bestows an unfair advantage! Scott acknowledges he didn’t invent the approach he advocates – winning golfers have always intuitively played this way and the seminal work of Mark Broadie introduced the metrics and optimization approach on which Scott’s Decade system rests – but he was the first to systematize it and teach it in a form that golfers could use in practice. He calls his system “Decade” because it’s meant to save its users the ten years that an attentive and intelligent golfer would take to arrive organically at the same understanding.

Shot Selection Under Uncertainty

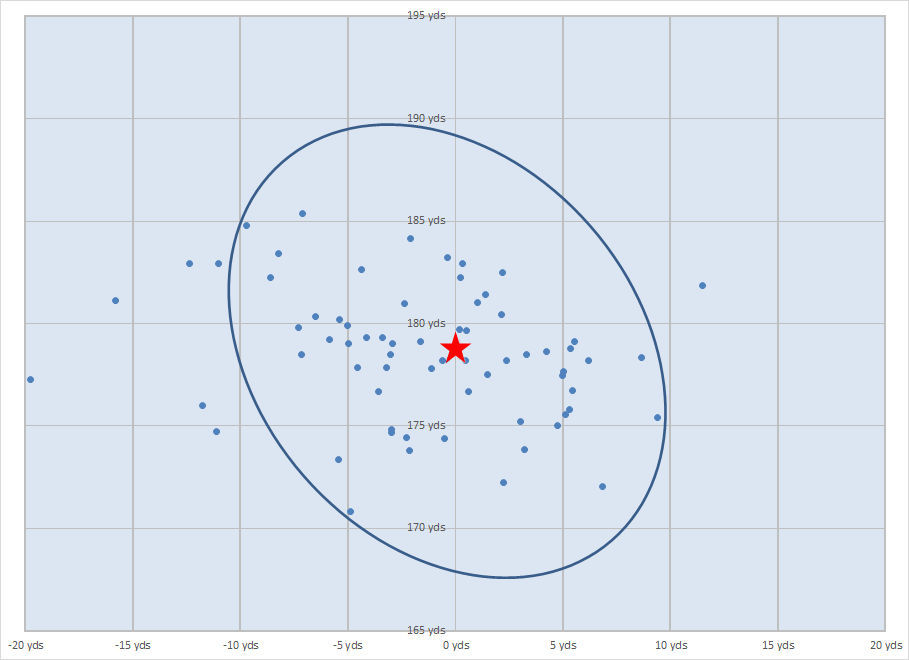

At the center of Scott’s approach are two core ideas: first, our decision-making needs to totally embrace uncertainty. We cannot make good golf decisions by focusing on the shot we want to hit, even if it’s the shot with the single most likely outcome, nor can we make a sound decision by focusing on avoiding the single worst outcome. The reality is that, even for a top pro golfer, there’s a wide range of possible outcomes for any given shot. We need to take account of all the places the ball can wind up after our shot, and their respective probabilities. In the chart below, we reproduce one of Scott’s most powerful exhibits. It’s the shot pattern of a scratch golfer (one of your authors, in fact), hitting 70 balls with a 7-iron at the target shown with a red star at a distance of 180 yards.

Shot Dispersion Pattern: Mark Hitting 70 Shots with a 7-iron, Targeting Red Star

Notice that not one of the shots finished on the target. When even a very good golfer stands over the ball, he needs to know it isn’t going to wind up where he wants it to go, not by a long shot! The standard deviation of this shot pattern is 6.2 yards left-to-right, and 3.2 yards short-to-long. Notice also the oblong pattern, indicating that a right-handed golfer tends to hit long balls to the left and short balls to the right, because the ball goes further when struck with a more closed club face. A golfer can get a shot dispersion pattern for each club, and each situation – fairway, rough or sand, wind or calm – which will provide a probability map of all the places where the ball can go.

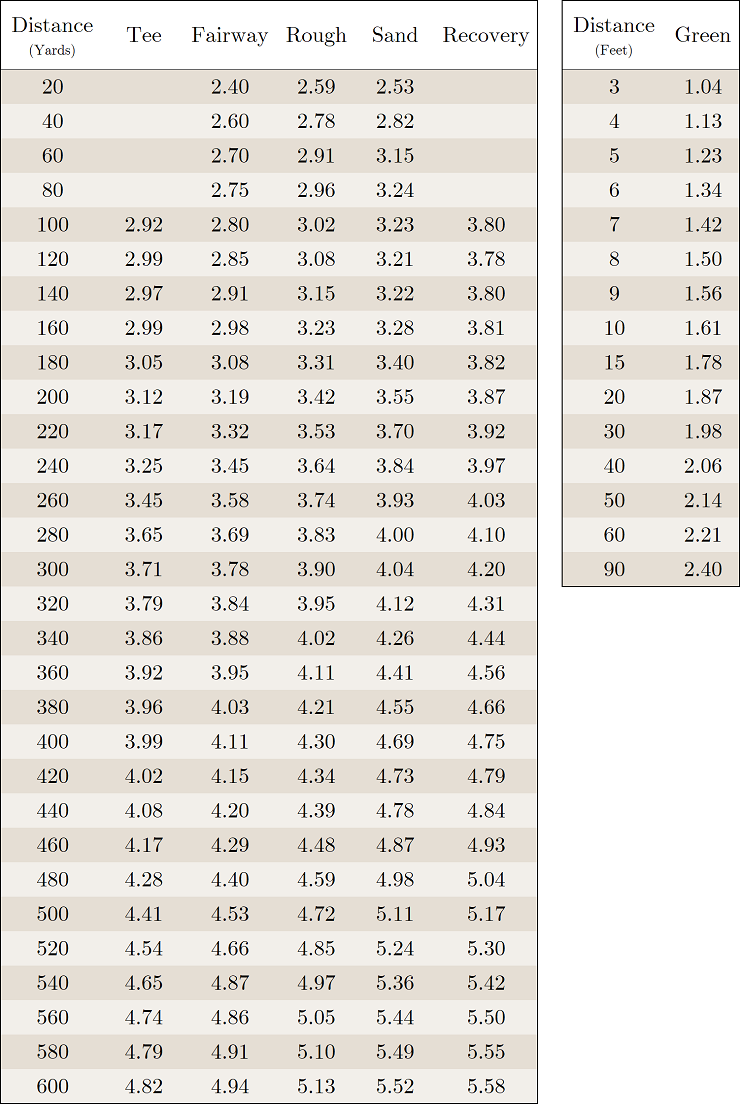

The second pillar of the approach is using a more sophisticated way of evaluating where the ball winds up than just measuring how close it is to the hole. Scott’s system relies on research done by Columbia Professor (and very good golfer) Mark Broadie. Mark is the inventor of the “Strokes Gained” method of measuring the value of each shot, which he shared with the golf world in his book Every Shot Counts (2014). He calculated, based on millions of actual shots hit by professional golfers, the average number of shots required to get the ball in the hole from just about every conceivable position on a golf course. For example, he calculated that a ball on the green, eight feet from the hole, takes 1.50 strokes on average to get in the hole – roughly even odds of a one-putt and a two-putt. Or, from the fairway 180 yards from the hole, it takes professionals 3.08 shots to get the ball in the hole.2 You’ll find a table showing these, and many more examples, in Appendix II at the end of this note.

Strokes Gained accounting provides a simple and powerful way to put a value on each possible outcome, which is much superior than using a system that is based solely on minimizing your distance from the hole after your shot. For each possible shot outcome from our current position, we just need to take the difference between the number of shots expected to finish the hole from the starting and ending position of our ball. So, if we’re 180 yards from the hole in the fairway, and we hit the ball 8 feet from the hole, we know the impact of that excellent shot was positive 0.58 strokes gained. We improved our position by 1.58 strokes, from 3.08 shots to finish the hole from 180 yards on the fairway to 1.50 shots to finish the hole when we’re on the green eight feet from the hole. It took us just one shot to improve our position by those 1.58 strokes, so this shot was worth 0.58 strokes gained.

The chart below shows the expected strokes to finish a hole for shots landing in various positions on and around the iconic green of the 18th hole at Pebble Beach.3 The green slopes down back to front, and left to right – so, if the ball winds up in the sand trap on the pin-side of the green, the expected number of shots to finish is 2.85, as it would be so difficult to get the ball to stop close enough to the hole to putt it in on the next shot. If the ball lands on the beach or in the ocean to the left, we count that as a 4.0, because a penalty of one stroke is assessed and the golfer will still be in a position from which he’ll need about 3 more shots to get the ball in the hole.4

18th Green, Pebble Beach.

Numbers in Green Represent Expected Number of Shots to Finish the Hole From Each Position

Now that we have a way of assigning a value to each possible shot outcome, we can calculate the value of shooting for any target, taking full account of the fact that there’s going to be quite a bit of dispersion in our shot outcome. We should choose the target that will leave us with the lowest expected number of strokes to finish the hole, which is equivalent to saying we should choose the target that gives us the highest expected strokes gained. The three illustrations below compare the expected outcomes for three possible targets that a golfer could select from 180 yards in the fairway.

Target = Pin.

Expected Shots to Finish Hole = 2.01.

Assumes Mark’s Shot Dispersion from Roughly 180 Yards Away in the Fairway

Target = Center of Green.

Expected Shots = 2.03.

Assumes Mark’s Shot Dispersion from Roughly 180 Yards Away in the Fairway

Target = Scott Fawcett Suggested Target.

Expected Shots to Finish Hole = 1.92.

Assumes Mark’s Shot Dispersion from Roughly 180 Yards Away in the Fairway

Choosing the pin as the target would result in the shot pattern represented in the first panel above. Notice that there are lots of balls that finish close to the hole, but that two balls would be on the beach or the ocean, and eleven balls would be in the sand trap left of the green – a tough spot to be in. Averaging over the 70 shot outcomes of Mark’s shots gives us 2.01 expected shots to finish the hole, using the pin as a target. While this is the target which would minimize the expected final distance of the ball from the hole, most seasoned golfers would recognize that it isn’t the optimal target. In the second panel above, we show the shot pattern if the golfer aimed at the dead center of the green, a target which has conventionally been considered the ‘smart’ and conservative shot. Here, the expected shots to finish the hole is 2.03, which is a little bit worse than aiming for the flag. Finally, we show the expected outcome choosing the target that Scott Fawcett’s system would recommend, which is a few yards to the right of and below the pin. Here we get 1.92 expected shots to finish the hole, a pickup of 0.09 expected strokes versus aiming at the flag.

An improvement of 0.09 shots may seem like a small amount of improvement from good decision-making – but picking up 0.09 strokes per shot on, say, 20 interesting shot situations per round can add 7 shots in a four-round tournament (0.09 x 20 x 4 = 7.2 shots), and can make the difference between a Top Ten finish versus middle of the pack.5

Of course, most golfers don’t carry strokes-gained tables, shot dispersion patterns, and computers around with them for making detailed expected-strokes-gained calculations for each possible shot target. This is where Fawcett’s Decade system comes in, providing decision-making heuristics players can follow in real-time on the course.

Scott the Financial Advisor

Scott’s insistence on taking uncertainty into account in making good decisions applies equally to golf and investing. We cannot reach good decisions by focusing on the base-case return of an investment. Instead, we need to weigh up all possible investment outcomes, the cost or benefit of each one to us, and the probability of each. And, just as we need the “Strokes Gained” accounting system to evaluate each possible shot outcome, we need to evaluate different monetary investment outcomes by the change they bring to our welfare – or Utility, as it’s called in economic theory.

Just as Scott tells us not to make golf decisions based on minimizing the expected distance from the hole after each shot, or alternatively, maximizing the number of birdies per round, so too in investing it’s important to choose the appropriate objective to maximize. In investing, making decisions that maximize the expected amount of money we’ll have can lead to poor, often nonsensical decisions. For example, maximizing expected wealth tells us to always take as much risk as we possibly can – using as much leverage as we can get – in any investment with a positive expected return. This is the policy which results in the highest expected wealth, but also results in a near-certain chance of going bankrupt sooner or later! The better objective is to make decisions that maximize our Expected Utility, which takes into account the fact that increasing amounts of wealth lead to smaller and smaller increases in our welfare.

In both golf and investing, we need to take account of the inherent, uncontrollable dispersion of outcomes, figure out what each outcome is worth to us, either to our golf score or to our personal welfare, and then find the decision which gives us the best expected overall outcome. Just as saving a mere 0.09 strokes on about one in four shots can add up to a very significant improvement over the course of a full golf tournament, in investing it’s also the case that small gains can add up to a big difference in outcomes. For example, a reduction of 0.75% in annual investment management fees over 40 years of saving and investing can result in 20% more savings to spend in retirement.

You might ask, “what if all golfers adopt Scott’s Decade system?” Naturally, it won’t provide the relative advantage it offers when few golfers are using it, but it will still represent the optimal approach to posting low scores. Investing, in contrast to a golf tournament, is not a zero-sum game, and so all investors can “win” from the application of good decision-making in investing. However, many of the cognitive biases that afflict golfers – the illusion of control, extrapolation bias, recency bias, overconfidence bias, and fallacy of the hot hand – also stand in the way of better investment decision-making. Scott has succeeded in giving us a system that makes golf a lot simpler, but he rightly warns us that embracing uncertainty and sticking with the program isn’t easy!

Relax and Enjoy the Ride

There’s a lot more to Scott’s system than what we’ve described here, and the deeper we dig the more of his wisdom and insights we find applicable to investing. Here are a few of Scott’s pearls of wisdom. We’ll let you decide whether they’re equally useful as applied to your investing:

- Eliminate the bogeys and birdies will take care of themselves.

- Don’t abandon your strategy just because you’ve had a run of bad outcomes.

- Keep things simple. Find the shot shape that’s natural for you, and stick with it. Hitting a good golf shot is already difficult enough without trying to put a different spin, trajectory and shape onto each shot.

- Almost never worry about how your opponents are doing. Make decisions that will lead to your best expected strokes gained outcome on each shot. It’s too confusing and complex and you don’t have enough information to strategically modify your play against your opponents.

- “The single most important thing I teach my students is expectation management.”

Players using Scott’s Decade system for reaching golf decisions report a feeling of calm and liberation from knowing they’re following a sound process and recognizing that they cannot control the individual shot outcomes. Accepting that their golf shots are more like the pattern of pellets from a shotgun, rather than a bullet from a rifle, gives them a totally different outlook and experience from a round of golf. It becomes all about making good decisions, and accepting that there’s just going to be a lot of luck – good and bad – in each round. But they know that, if they keep making good decisions, they’ll make the most of whatever technical skill they have in the long-run and be able to accept the ups and downs along the way with greater equanimity.

Appendix I: Does It Make Sense to Give Up Expected Shots to Add Variability?

As Scott says, “The bottom-line of game theory in golf is that it is exhausting to constantly try to run iterations of finishing positions AND find situations where you can increase your scoring variance WITHOUT destroying your overall expected score.” It may seem like a good idea to accept a worse expected score in exchange for greater score variability, since money payoffs in golf tournaments are a convex function of finishing place. However, we agree with Scott that it’s unlikely to be the right thing to do in most cases. For example, a casual look at the payouts for the 2021 US Open at Torrey Pines suggests that if it cost 0.5 expected shots to generate two shots of extra variability per round, it generally would not pay to go for higher variability.

Bear in mind that the normal variability in a round of golf for a tour player is 2 to 3 strokes per round – holding course, condition and golfer form constant – so intentionally adding two shots of variability would be a pretty big deviation from optimal play. A fuller analysis would also bring risk-aversion – via the player’s Utility function – into the analysis, which will further push against the idea of accepting a worse expected score for higher variability. We agree with Scott’s advice to keep it simple in golf, and we think it applies to investing too: “…saving your energy and just sticking to the system is the optimal play for almost everyone.”

Appendix II: Average Number of Shots a PGA Tour Player Takes to Hole Out from Various Lies and Distances from the Hole

For example, starting from the tee 400 yards from the hole, PGA Tour pros average 3.99 strokes to hole out. Starting on the green eight feet from the hole, the PGA Tour average strokes to hole out is 1.50. A recovery is an obstructed shot to the hole, e.g., a shot from behind a tree that forces a pitch back to the fairway. Reproduced with permission from Mark Broadie from his book Every Shot Counts (2014).

Further Reading and References

- Broadie, Mark. Every Shot Counts: Using the Revolutionary Strokes Gained Approach to Improve Your Golf Performance and Strategy. Avery. 2014.

- Broadie, Mark, “Assessing Golfer Performance on the PGA TOUR,” Interfaces, Vol. 42, No. 2, 146-65. 2012.

- Rapaport, Daniel. “Has This Data Nerd Created a Golf Cheat Code?” Golf Digest. 2021.

- Scott Fawcett’s Decade Elite online program.

- Victor is the founder and CIO of Elm Partners and James is Elm’s CEO. Mark is pursuing a Masters degree in Data Science and is a captain of the golf team at the University of Pennsylvania.

The authors thank golf strategy experts Mark Broadie and Scott Fawcett for their foundational work that made this note possible, and for their helpeful comments on this note. Thanks also to Larry Bernstein, Jonathan Garrick, Larry Hilibrand, Peter Hirsch and Cade Massey for reading a draft of this note and sharing their comments, and thanks to our Elm colleague Steven Schneider for doing such an artistic job with the exhibits. Of course, any errors rest with the authors. This note is not an offer or solicitation to invest.

- Strokes Gained data for college golfers is also available, but most people use the numbers for the PGA tour players.

- The pin position is from the first round of the 2019 US Open.

- We’ve made a conservative approximation here in that the golfer might be able to hit a shot from the beach if he finds his ball in a good location, or depending on where his ball goes out of play, he may be in a position where his expected strokes to finish the hole could be somewhat below 3.

- Also, seven shots made the difference between winning the 2021 US Open vs tying for 15th place.

Previous

Previous