July 2024 Investor Call Q&A with Victor, James & Jerry

By Victor Haghani, James White & Jerry Bell

Victor Haghani: Welcome everybody! Looking forward to today’s semi-annual investor call. For everybody who’s an England football fan – congratulations to all of us! Yesterday was a very, very happy day in my family, and I’m sure for lots of people on the call, it was really remarkable and kind of wonderful. Even people who aren’t England fans, I’m sure a lot of people will be watching Sunday for the Euro 2024 Finals, so fingers crossed for England.

First of all, today’s call is going to be a tiny bit different than what we’ve done over the past few years. The first thing is that Jerry, our newest third partner joining me and James, is going to introduce himself. We’re super excited to have Jerry on board and expanding our partnership by 50% as we continue to grow and try to do a better job. Jerry has already been instrumental in helping us to improve everything that we’re doing and we’re really, really happy to have him on board. So he’s going to introduce himself, then James is going to do a quick review of the first half of this year in terms of asset allocation and lots of other things, then I’m going to talk about some potential new Elm inititives, and then we’ll get into Q&A. So yeah, welcome everybody – excited to have so many of you on board. Jerry, why don’t you take over from here for a little bit?

Jerry Bell: Absolutely, thanks Victor. I’ve already had the pleasure of meeting a handful of people on the call, which is great. A little bit about my background: I joined the team a little earlier this year, so I’ve been here about 3 months, which feels like it’s flown by. I started my career in asset management at JP Morgan, where I worked on managed portfolios for private clients and some small institutions. I did that for a few years; after leaving JP, I took a little bit of a turn and actually helped build out and operate an AI startup in the media and advertising space. I did that for about eight years, and left towards the end of last year when I met Victor and James. I actually think that my story, about meeting the guys and reading the book, is actually quite similar to what I’ve heard a lot of people talk about. Obviously, the philosophy of Elm really resonated with me, and I’ve been trying to do a lot of these principles in my own very limited capacity, but kind of lack the ability to really do it in any sort of systematic way. And so, learning about Elm, learning about the approach, it really made sense. It’s been nice to kind of hear that come up time and time again as we meet new prospects and clients and hear how they found us and what was appealing to them.

To give a little bit of an overview of what I’m focused on: I guess the easiest way to think about it is I’m really trying to help answer some big questions. One of the main ones is how do we generally improve the overall Elm client experience and improve client outcomes? As we continue to grow, we’ll have more resources to improve our offering, but how do we keep the ethos and the principles of Elm intact, and keep it feeling like the same offering that this group has found value in over time? If we think about our investor base to date – we’ve mostly been early adopters. These are people who are interested in trying new things, new approaches are appealing to them – but there’s this big chasm between early adopters and the early majority of people who adopt a product. The same kind of tactics and approaches that are appealing to early adopters sometimes don’t appeal to an early majority, and so you have to continue to evolve the product, all the ways you talk about yourself, the way you show the value of what you’re doing. It has to continue and evolve, and one of the things I’m really focused on is helping think through that with the guys.

Second: how do we continue to support this diversifying client base? Since the release of The Missing Billionaires, naturally, the client base has started to touch a lot of different industries, different geographies, different levels of investing experience. We think and hope this trend will continue, but it’s going to require an evolution of the story, evolution of the product offering, and we’ll continue to evolve Elm to help appeal to all different sensibilities and types of clients.

Lastly, and probably most importantly: how do I continue to help free up time on Victor and James’ calendars? Taking a lot of the day-to-day client management and minutiae off of their plate so they can continue to spend time on research and thought pieces and (Lord willing) writing another book at some point in the future – not that I’ve signed them up for that at any point.

Those are the big things I’m focused on. I do have an ask for this group and something I would love help with: as I continue to get onboarded, I really would like to know what you like about Elm, what you don’t like about Elm, what you think people who don’t know about us – your friends, your colleagues, your contemporaries, etcetera – should know about Elm? When you’re talking about us and to other people, what do you think is really valuable about us? I think that would be super-valuable and something that we’re always trying to get more of; I’d love to hear about all of that. Of course, as the new guy, I don’t have the burden of responsibility for any things that have happened in the past, and so it can bring a fresh perspective and that’s really exciting.

That’s what I’m focused on. Like I said, I’ve met a few people on the call, but obviously would love to continue to meet as many as possible. I’m splitting time between New York and Philadelphia, so the folks on the East Coast here – generally very, very happy and available to meet if if the opportunity comes up.

VH:

Right, James, you’re up.

James White:

Great. Well, I’m 50% of the burden of responsibility – and one of those responsibilities is reviewing the asset allocation. This is all going to be old hat for our longtime investors, but we have enough new investors that we wanted to review some of the tools we have available on the website.

One of those is our Asset Allocation tool. This is a tool we use for ourselves virtually every day, and you can both see the allocation at one moment in time for any combination of dial settings, or you can see the allocation historically for any combination of dial settings. As you can see, the asset allocations over the year so far have been quite boring. Overall equity allocations have been, for these settings, quite close to target. The biggest change over the period is really within fixed income, the mix between TIPS and bills. At various times, we’ve had a lot of bills and a little bit of bills – but overall, the broad equity allocation has been pretty static and reflective of the fact that (especially in the US) the signals we use are mixed, momentum is fully positive but risk premia are pretty tight. For the details, you can just look at one day where we show the baseline allocations, the target allocations, the breakdown of baseline deviations from risk premia and momentum/risk level and then the signals themselves. There’s also a glossary here to explain some of what’s going on.

We have a few other tools that are useful to people. There’s a Tax Calculator that tries to take a utility perspective on the question of, “When is it worthwhile to realize gains early or not?” It’s not deeply self-explanatory, but we do have a note that we wrote on it back in the dawn of time. Anyone who’s interested in it, just ask us and we can send that to you.

The Endowment Calculator basically models the Merton portfolio problem. There’s a fair number of people out there who seem to be attempting to live forever and pay no taxes, and this is for you. The simplest solution to the to the portfolio choice problem assumes infinite life and no taxes, and this just cranks through that. So, if that’s your hope, you can use this one.

If you’re a mortal, like me, then this Portfolio Calculator basically cranks through the portfolio choice problem, given things like mortality and taxes and unreasonable things like that, where you can put in quite a lot of detail about about yourself. We’ve been using this tool, walking people through it for quite a while now, and we’re sufficiently pleased with it the value people say they’re getting out of it.

We’re now starting to offer a more formal portfolio choice process that we’re charging $5,000 for, and we focus primarily on the big picture policy questions of, “What should your optimal investing and spending policy be?” But there are more bespoke questions we may be able to focus on also. What’s the optimal point to retire for a young person with a very volatile income? How much house can you buy? How much can you spend? And, depending on your particular situation, we may use this tool (which is public on the website) or we may use our model, which is sitting behind this tool and is more flexible than what’s available in the web tool. Either way, we expect one of the outcomes of the process will be, going forward, you’ll be comfortable just using this tool on your own and you won’t need to ask us every time you want to update update something. Anyone who’s interested in that, please let me know, let Jerry know. We’ve been really pleased by the value people have felt they’re getting out of it. Sometimes I think half of the value just comes from forcing people to sit down and figure out what they’re spending, which is often surprise to people.

One tool which is available to all investors, but which is not on the website, is the Returns Viewer. For compliance reasons, it’s not on the public website – if you need the link, just ask us for it; it’s also included in every quarterly letter. Those are the main tools we have on the website. Next, Victor is going to talk about a bunch of new initiatives at Elm – but before he does, I’m going to steal his thunder a little bit and talk about something we’ve recently started doing.

Historically, when clients contribute appreciated assets, we’ve had a policy of, if there are assets that are close matches to existing buckets, we’ll take them – if they’re not, we just can’t take them. We’ve significantly broadened what we’re willing to take, where now people can give us very large portfolios of existing appreciated assets, and we can do custom mappings for all or part of them to our existing buckets, including large portfolios of single-name stock. For example, we had a client who pretty recently gave us a portfolio of hundreds of single-name US stocks and we mapped them to the appropriate US sectors. Going forward, we treat each one basically like it’s just an ETF mapped to that sector. So, if we need to sell something in taxable accounts, we’ll look for the stock with the lowest gains and we’ll sell that. Whenever we need to buy, we’ll buy with the appropriate ETF rather than buying single-name stocks. Our system will keep the portfolio close to our sector targets or to the broad market targets as it rebalances and tax-loss harvests. What it won’t do is, if you give us a portfolio of hundreds of stocks – as we rebalance those stocks, we’re trying to keep them close to a particular index. If we do the sector strategy, we’ll try to keep the overall sector weights about right, but in deciding which individual stock to sell (if we need to sell something) the only consideration is taxes. So, we’ll sell losses first and then gains, and we’ll try to avoid selling short-term and high long-term gains as we do with anything else. We’ve already had a number of clients for whom that’s been useful, and we’re happy to talk more about the details of that anytime.

VH:

One thing I just want to clarify with what James was saying: that has to do with our Separately Managed Account clients, not our offshore or onshore fund investors. In general, we have all kinds of clients on the calls, but I’m about to launch into some stuff that’s going to pertain to one class of our investors, but we think that it makes sense for everybody to hear about these different initiatives.

I’m going to talk about three things that we’re working on right now. One is the potential integration of an adjusted CAPE measure, taking account of the fact that companies don’t pay out all their earnings as dividends. I’m going to talk about an initiative that we’re working on and potentially converting our US private fund into a publicly-traded ETF. Then, a third initiative that we’re working on is trying to publish some useful data for all of our investors that people probably find hard to find in major financial publications.

We sent out this note a couple of weeks ago: “Introducing P-CAPE” aka payout-adjusted cyclically-adjusted price earnings ratio. What we described in there is that the Schiller-Campbell Cape measure uses, for cyclically-adjusted earnings, just the last ten years of average earnings adjusted for inflation – but I think everybody realizes that when companies are not paying out all of their earnings as dividends, they’re going to use that amount that’s not paid out either to invest in trying to grow their earnings and their business or in stock buybacks. A long time ago, companies paid out 2/3 of their earnings as dividends, but particularly in the US recently, companies have been paying out just 20% or 30% of their earnings as dividends. We think that really underestimates what cyclically-adjusted earnings is trying to do, which is to give us a good estimate, averaged through the cycle, as we look forward.

We wrote this and got a lot of good feedback from people on it. Everybody kind of felt that it made sense and really ties into the kind of earnings growth that we’ve seen over the last 100 years in the US, or the last 50 years in non-US markets. It does a better job of predicting earnings over the long term than just averaging the earnings inflation adjusted by itself. We’re in the process of looking to integrate this into production. It would result in higher equity exposures, on average, across the different buckets – sometimes, that’s pretty modest, other times we could be in environments where it’s a bit more significant. Anyways, we’ll keep you posted, we were thinking of bringing it in over the course of the rest of the year perhaps.

The second thing that we’re working on is – the first thing that we did when we started Elm at the end of 2011 is we set up a private fund to look like a hedge fund, except it was charging 12 basis points, making it not a hedge fund. That was what my family and all of our early friends and investors invested in because we didn’t start doing Separately Managed Accounts until about five or six years later down the road, when things got to be such that we could do that. So we had this private fund from the end of 2011 (we also have a fund for non-US investors, but that’s separate) but once we started doing SMAs, people liked our Separately Managed Accounts more than putting more money into the fund, and so the fund has been kind of static. Sometimes people redeem, but the market’s been growing, so it’s been fairly static in assets – but a number of our investors have said, “Gosh, I wish that this would be either in the form of the underlying ETF, I wish you could convert this into a Separately Managed Account, I wish that it were in ETF.” And so, we’ve been looking to convert our private fund, Elm Partners Portfolio LLC, into an ETF over the last several years.

We’re working with US bank, we’re working with the New York Stock Exchange. We think it’s likely – certainly plausible – that we can succeed in doing this. We actually have a ticker allocated to us, ELM would be the ticker if we do the ETF conversion. As we wrote in our letter to our US Fund investors, there’s a lot of good benefits for making the conversion. There’s a few potential negatives, but we think on balance it’s a big positive if we can do it effectively and cost-efficiently. Not only does it have daily liquidity, but the maybe the best part about it is it becomes very tax efficient. We all know that ETFs have a lot of long-term tax efficiency to them, so you’re even more tax efficient than being in the private fund structure. We also hope it’s going to generate economies of scale, and maybe even lower costs down the road, even though the cost of our private fund are quite low right now. Anyway, we’re going to have a separate call for all fund investors; please feel free to be in touch with me or James or Jerry with questions about the conversion as we’re thinking about it – we haven’t decided to do it, but we’re really strongly considering it and we’re really excited about it.

The third thing that we’re planning on doing is that, for a long time, we’ve said that the most important pieces of information that people need to invest sensibly is they need some idea of the long-term expected return of stocks and long-term expected return of safe assets like TIPS (we like to think of TIPS being that relevant asset) and it’s really hard to find those numbers; they’re not printed in the Wall Street Journal. We wrote an article a long time ago, “The Most Important Number Not in the Wall Street Journal,” which we said was cyclically-adjusted earnings yield of the different markets you might invest in. And so, we’re thinking about a quarterly e-mail to all of our investors and followers with a bunch of information in it that people find hard to get from mainstream financial publications. We’d have cyclically-adjusted earnings yields for the different major markets in there, we’d have real rates for TIPS, and maybe some of the other markets that are a little bit tricky to find. Please let us know if there’s other things that you think would be really great to have in there that you’re finding it difficult to find elsewhere. We’re planning on doing that on a quarterly basis, and we hope it doesn’t create too much extra e-mail for you, and we’ll probably also have a link where we’ll have more updated numbers during the quarter.

So those are the three initiatives that were that we’re working on, and we’re happy to take questions on those as well. Now we’re going to go into the next segment, which is trying to answer questions that people have sent in or are sending in now, etcetera.

JB:

James, going back to the single stocks: if someone were to give you a stock that has appreciated a lot, how do you make the trade off between diversification and taxes as we optimize going forward?

JW:

We wrote “How Much Should the Tax Tail Wag the Asset Allocation Dog?” quite a long time ago – I won’t get into all the detail of, but this gets into the utility theory behind how to offset a realized gain versus being away from your risk targets. The short answer is, if it’s a short-term gain, it’s much more tolerable to stay far away from your risk targets; if it’s a long-term gain, the optimal solution usually looks like going part of the way to your target, but not all the way there. What our system will do is, not solve the full utility problem every time, but it’ll try to keep your portfolio in the vicinity of our asset allocation targets and to do that in a way which will minimize the realized gains. So if the stock is the highest appreciated asset in your portfolio, it would be the last thing we sell – but ultimately, we wouldn’t let your portfolio get massively away from our asset allocation target. That’s how it’s set up now.

VH:

People have asked us about doing a kind of distribution from the fund, and we’ve really found that we’d need to do it for everybody at the same time, and we don’t think everybody would be on board for that. We also feel that the ETF is a better solution from a tax point of view than the income distribution for people that like that asset allocation and want to go forward. We think that this is the most practical of the different options of leaving the fund as it is, doing a full in kind distribution that we need everybody to be on board with, or the ETF. We think that the ETF is the best of the three options, although we still haven’t fully decided on that. We’re happy to talk about that more offline as well. A few people that I think that was the start of this process towards the ETF was people saying, “Geez, I’d really like to have something in a Separately Managed Account. I could then use it as collateral, etcetera,” and we think this is going to be a better solution – but again, happy to talk about that offline.

JB:

One question that we got from a number of different folks is touching on how we feel about the concentration of MAG 7 and broad indices and what do we make of that – how do we think about cyclically-adjusted earnings yield, does it change our perspective on it? Are we missing something fundamental as the problems of MAG 7 brought in the indices that we invest in?

JW:

It will shock you to learn we already wrote a note about this also. It’s called “Are Market Capitalization Weighted Indicies Too Concentrated in the Biggest Stocks?” from 2021. This is not a new topic; it’s gotten a little bit more extreme since we wrote about it in ’21, and I recommend this note to everyone. Our thought process had a few different threads to it: first, as we think of it personally, we find it useful to realize that all of our portfolios are much broader than just the S&P. Even just the US market is much broader than the S&P – we also have fixed income, real estate, human capital for those who aren’t retired, non-US equities. You can use the dials to set how much US or non-US equities you want, but the vast majority of our investors have quite global portfolios, and so the further out you get, the less the concentration looks like it’s really a problem.

Another thread that we looked at is that these indices being quite concentrated and quite a lot of the market cap and net returns coming from a small number of names is not unusual. It is not as historically anomalous as it feels right now.

Then the third thread is, we just looked at the philosophical basis of how much extra return is needed to make having different levels of concentration in a small number of names optimal? And it turns out that the extra return you need over the average return is quite low formally – and we go through that argument in detail in that paper. So, all of those things conspire to make us feel like it’s obviously an important feature of the current investment environment, but it’s not something we specifically, worry about.

JB:

Victor, could you talk a little bit about direct indexing and tax loss harvesting in general? This is a question we get all the time; in the financial media, there was a story last week about how much JP Morgan’s tax direct indexing products have grown. Just talk a little bit about that and what the Elm perspective is there.

VH:

Talking about US taxable investors, it seems as though the direct indexing tax loss harvesting product has had tremendous growth over these past years with Goldman, Morgan Stanley, JP Morgan and others really pushing this to their client base. Tax efficiency for taxable investors, as we always say, is like the same as fees. It’s something that is a low-hanging fruit that we should really try to get as much tax efficiency for our clients as possible, just as we want to have the lowest fees possible too. Reducing fees and taxes is worth more than trying to take risk to increase returns. So we’re doing tax loss harvesting, we’ve been doing tax loss harvesting within our private fund and SMAs from the very beginning. Bottom line, we think that, for most typical investors that invest in Elm where most of their taxable income is going to be in the form of long-term capital gains, they don’t have a lot of short-term capital gains that they’re getting.

The comments I’m about to make are for people who most of their capital gains is going to be long-term capital gains. For people who have a ton of short term gains, there are programs with direct indexing that can be very valuable in converting short-term gains into long-term gains, but I’m going to put that to the side for the moment. It’s something we can help with, we just haven’t had people come to us and say, “Here’s my problem: I have a lot of short term things, can you help me convert them to long-term gains?” We know those people are out there, but they’re not so much in our circle.

If you’re that sort of typical investor, then direct indexing and tax loss harvesting in general is trying to help you to get more deferral. It’s helping you to defer net realizations into the future. Now, just by owning equities, there’s a certain amount of deferral that’s happening without having to do any tax harvesting. If you have a relatively static portfolio, you’re going to get a lot of deferral anyway and don’t necessarily even need tax loss harvesting to make that better; it’s going to be very good aleady. However, if you have appreciated assets, or if you want to reduce and get into more diversified holdings, or if you’re doing a dynamic asset allocation the way that we are, then you’re going to start to have some amount of capital gains coming in over time. Tax loss harvesting is going to be really helpful in deferring those.

Now, when I say helpful, it’s going to be helpful in deferring those as long as you feel that your future tax rate is not going to be higher on a risk-adjusted basis than your current tax rate, and that’s a really big “if” for people. Certainly if you’re in a high-tax jurisdiction like California and you plan on moving to Austin, you might want to try to defer things because you’re pretty sure that if you can do that soon, that you’re going to be in a lower tax rate when you do realize things – but if you’re subject primarily to the federal tax rate or you’re not planning on moving, maybe you actually think the tax rates are going to be higher in the future. These are some mitigations on it.

Now I’ve just come to the to the main comment here, which is that tax loss harvesting with individual stocks – all else equal, in a perfect world, individual stocks are about twice as volatile as indexes are. If you’re doing individual stock tax loss harvesting, you should expect to generate two times the tax loss harvests then you would get by doing it with ETFs on indexes that are half as volatile. However, in practice, all of these direct indexing programs want to put some limits onto your tracking error. Why do you have tracking error with the individual stock tax loss harvesting? It’s because of the wash sale rule: if Apple has gone down and you want to sell that, you sell it but you can’t buy it for 30 days, and you’re going to have this period of time where you’re underweight Apple, you’re overweight something else and you’re going to want to have some kind of limits on how much tracking error versus your index you’re willing to take. That means that you’re not getting that full two times as much expected tax loss harvesting – that’s the first thing.

Second thing is you’ve got all this tracking error and when that tracking error is negative, when you’re underperforming the index, you’re going to be really upset about that. Not only are you going to be upset, you’re going to believe that something systematically bad is happening to you – and it might well be the case that something systematically bad is happening to you, in the sense that there’s a trillion dollars of people out there that are selling losers and waiting to buy them back; it’s certainly plausible that the Citadels of the world and the rent techs and so on, part of where they’re generating their profit is knowing that there’s a lot of individual direct index tax loss harvesting that’s going on. So we spent several years building tools, building systems to do individual tax loss harvesting, we thought it was a really big deal that we wanted to provide to people…but after even running our own money just to get a feeling for how it was going to be, we’ve decided to mothball it. We’ve sort of put it on the side, we have a system that works, but we’re not really enthusiastic about it. We think that tax loss harvesting within the context of what we’re doing at Elm is very good; there’s no tracking error –

JW:

Almost no tracking error.

VH:

Sorry, almost no tracking error or very little tracking error. For people who want more tax loss harvesting within our Separately Managed Accounts, we can break up the US into its into its 11 sectors, that gives it a little more volatility, a little bit more harvesting. For people that are more concerned about the tax characteristics, SMA investors can turn down the dynamic dial from say, 100% down to 50% and then the trading that we’re doing is going to be roughly half as much and the tax loss harvesting is going to be on the whole portfolio – that would even take you closer to the tax efficiency of just the buy-and-hold or static weight portfolio. We’re going to be writing more about this, but we really think that direct indexing tax loss harvesting is something that is being oversold by the purveyors of it in a very significant way – we think that with what we’re doing, we can get people almost the same kind of tax efficiency, almost the same set of benefits. If somebody says, “I want to do direct index tax loss harvesting because I have an appreciated holding in the company that I work at.” OK, we can break your US index into sectors, we can drop out technology from that and get you to a similar place than if you’re doing direct indexing and they said, “OK, let’s not give you any stocks in that sector.” Long answer, but we’re very tax aware and we’re thinking about it a lot – and again, happy to elaborate more offline with people.

JB:

To your earliest point, why don’t we get a bit more of a global perspective and do David’s question in the chat about risk premium in the US broad equities and how adopting P-CAPE may change or impact our views of other of other markets.

VH:

I think one of the most common questions that we’ve been getting over the last 10 years is, “What are we missing that the US equities are outperforming non-US equities?” And yet, we say that the earnings yield of non-US equities is higher than the earnings yield of US equities, and then we tend to be overweight in non-US equities relative to people’s baseline and underweight US equity – that’s not always the case, but in general, that’s kind of the configuration we’ve been running in for quite a long time now. First of all, this hasn’t always been the case – historically, if we go back 20 or 30 years, the earnings yield of US equities was higher then the earnings yield of non-US equities. People priced international equities and non-US equities at a higher multiple and a lower earnings yield than US equities, but over the last two or three decades, the multiple expansion in the US has been sort of a constant and the multiples in the rest of the world have increased, but not nearly as much as in the US.

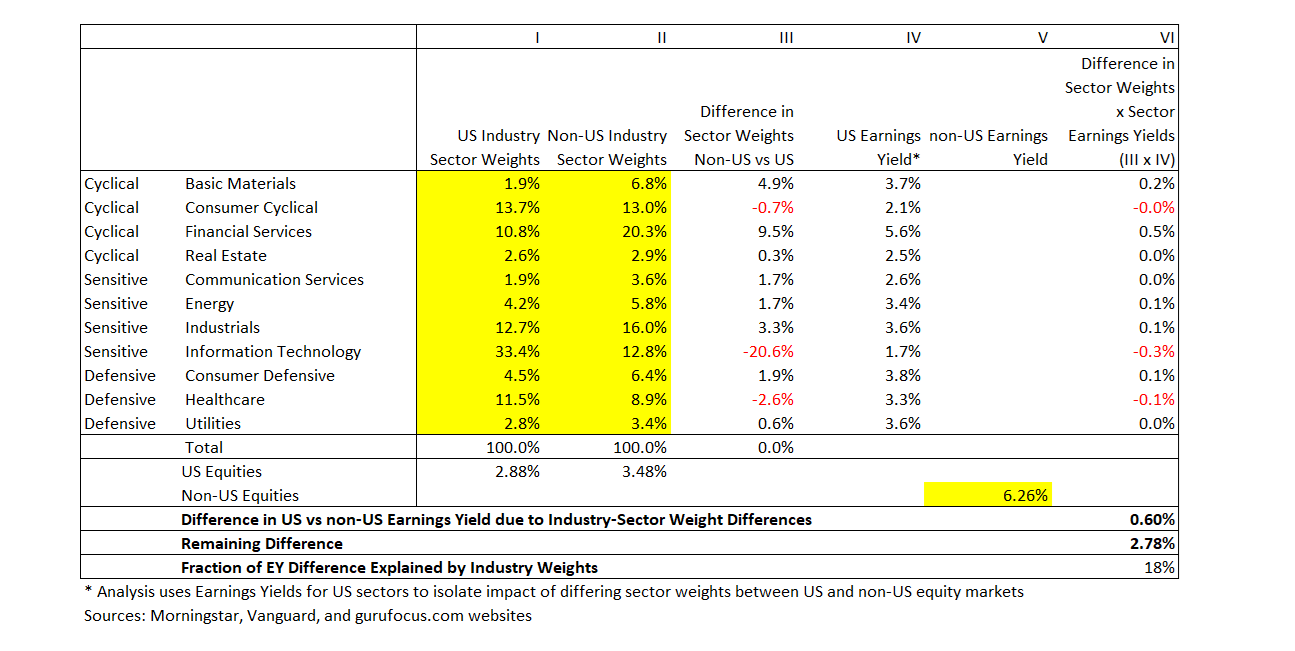

One question that we’ve gotten a lot is, “Are we missing something in the fact that the sector composition of the US is so different than the rest of the world?” And we’ve written about this, we’ve shown this analysis, we just updated it for today’s call. This is one way of looking at that and seeing how big the sector differences are in terms of affecting the earnings yield that we’re seeing. So today, what we see is that the US has an earnings yield of around 3%, i.e. it has a cyclically-adjusted multiple of over 30 and the rest of the world has a cyclically-adjusted earnings yield of about 6.3% – twice as much as the US earnings yield on a weighted average. Which is a multiple of what, 16-ish? Something like that. In this picture here:

What we’re showing is that the difference in US industry weights versus industry weights in the rest of the world. You can see about 2/3 of the way down the listing – information technology, 33.4% in the US (that’s Google and Meta and whatever) and 12.8% in the rest of the world. It’s almost three times a bigger sector weight in the US versus the rest of the world. So, we have all these different sector weights – one really simple thing to say is, “What if the US had the same sector weights as the rest of the world instead of the actual sector weights?” What we find is that, instead of the earnings yield of US equities being 2.88%, it would be 3.48%. Indeed, the sector composition is explaining part of the difference in the multiples or the earnings yield between US and non-US equities, but it’s not explaining that much of it. It’s explaining .6% of the earnings yield difference, but the total earnings yield difference is over 3%, so it’s only explaining 18% of the earnings yield difference, the sector differences between US and non-US equities.

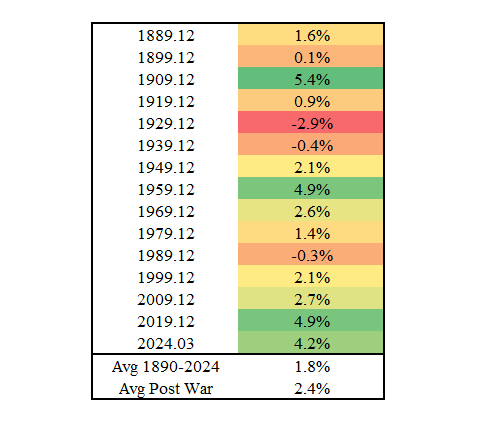

People might say, “But isn’t the technology sector in the US just better than the technology sector in the rest of the world?” Sure, it might be, but the other thing that we’ve pointed out is that this US outperformance over the last 20 or 30 years is not coming from massively better earnings growth in the US once we adjust for payout ratios and a little bit the currency – it’s not coming from that. It’s coming from a multiple expansion that people are believing that US equities earnings are going to grow much faster, but historically, they haven’t. Here’s the per annum earnings yield growth for US equities from Professor Schiller’s data going back over 130 years:

You can see that earnings growth in the US over the last 130 years has been 1.8% per annum. Now, given that US companies paid out only 50% or 60% of their earnings on average over the whole period – as we wrote in our P-CAPE note, you would expect there to be earnings growth because they’re keeping earnings back and investing that back into their businesses or in stock buybacks more recently. That 1.8% growth over the whole period is very well explained by companies keeping earnings back in the company and growing earnings with that money by like 5% a year or something like that, which has been the real return of the US equity market and the average earnings yield. Even in the post-war period, where we have that huge jump in earnings following the Second World War where we had this 4.9% per annum growth in corporate earnings – even including that, we’ve been running at 2.4% for like the last 60 years. Indeed, since the year 2000, earnings growth in the US has probably averaged 3.5%, but that 3.5% is totally explained by the fact that US companies are only paying out 30% or 35% of their earnings over that period as dividends, and the other 65% they’re investing back in their company or they’re doing stock buybacks and reducing the number of shares. So, we don’t think that earnings yield is broken as a predictor, we think earnings yield makes sense. Yes, we could try to do sector adjustments to all of our earnings yields – maybe it’s something we should do, or will do – but we don’t think it’s really a big enough effect to warrant it right now, and it’s something that we do think about.

David Posen:

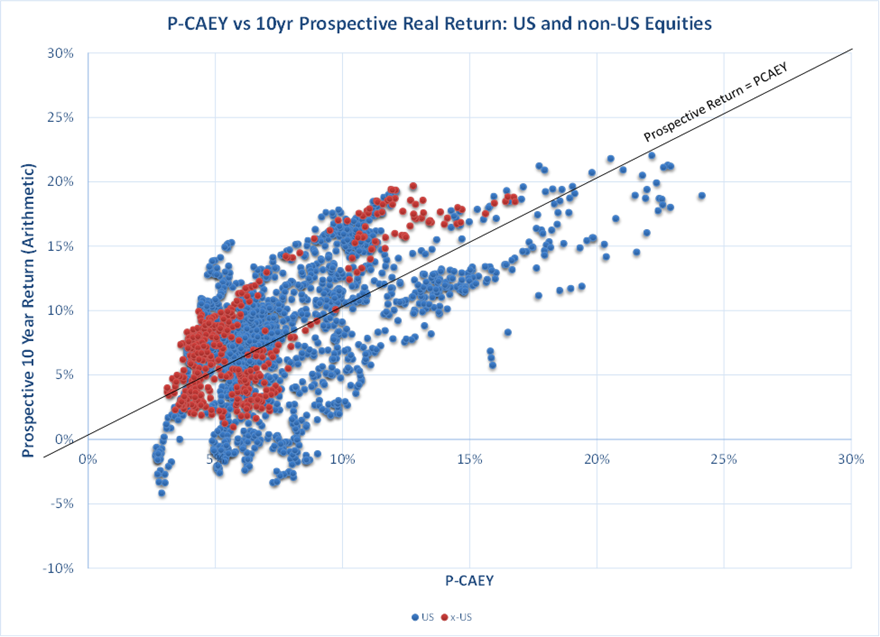

Victor, that’s very helpful, and as you say, it answers a range of questions. Is the difference in payout ratio between the US – which you say has been dropping from 2/3 down to 30% – is it materially different than the payout ratio in the rest of the world? When you incorporate that into your P-CAPE, will it account for some of the apparently large difference when one looks strictly at earnings yield using CAPE ratios, is that part of the explanation? I love that shot that you provided in your P-CAPE report demonstrating the tight relationship between cyclically-adjusted earnings yield and subsequent ten-year real returns, but I was just wondering how broadly distributed that is – is that a tight fit, or is that an average? And, frankly if the earnings yield is 3% now in the US, the real return over the next ten years could be an extremely wide range around any single point estimate.

JW:

The short answer is it’s a wide spread. You can see here:

Neither CAPE nor P-CAPE explains the majority of long-term returns – it’s just a relatively unbiased estimator of long-term returns – so we think it’s the most robust, systematic, best long-term thing you can do. It would be weird if it wasn’t a wide spread because there’s just so much that can happen in ten years, there’s an unbelievable amount of noise in the world – but, for asset allocation and systematic purposes, I would say the important thing about both CAPE, cyclically-adjusted earnings yield and build- and payout-adjusted cyclically-adjusted earnings yield is that, as estimators, they do have significant power and they’re relatively unbiased. One point Victor and I were talking about about recently – to your first question – that I think is a little counterintuitive to people is that, actually, if you look at all the different global markets and the relatively recent performance of earnings yield as a forecaster, for the non-US markets, it’s done quite well. The US is really the outlier, where US performance has been dramatically better than earnings yield would indicate. As Victor said, that’s really because of the of the dramatic multiple expansion. It’s not because earnings have been so much better. It’s just because multiples have expanded dramatically.

JB:

One of my most important roles is that I’m Time Keeper, so we’re gonna do one question for James. There’s been a lot of great press for The Missing Billionaires – a glowing review in the Wall Street Journal, a great review in the Economist. What is the biggest pushback that you have heard to The Missing Billionaires?

JW:

There’s a variety of things. I’m heartened to say we’ve gotten a lot less pushback than we expected, really dramatically less – and I don’t think it’s because people are trying to spare our feelings. Probably the biggest systematic pushback we get is around estimating return distributions and outcome distributions, and a question about whether the inputs are available to use the framework we talk about. A good number of people seem to have a view that returns are just radically uncertain and that outcomes are radically uncertain, and you just can’t do anything to estimate them or model them. I have two responses to that: my first one is how do you invest in anything then? I mean, if you just have no estimate for what the distribution of returns is going to be for anything, then how can you invest in anything?

My second response is: we think there’s a continuum of assets that ranges from highly-estimated able return distributions to really hard-to-estimate return distribution. At the highly-estimated end of the spectrum, we would put TIPS held to maturity or even nominal bonds held to maturity in nominal terms. Bonds not held to maturity would be pretty close to there; broad equity markets, through things like P-CAPE and CAPE. We think the the individual outcomes are hard to know – but the nature of the return distributions, the center of the distribution, the volatility of the distribution, the general character of the tails – isn’t knowable with absolute precision, of course, but we think you can certainly do a good enough job to get good results. Then, further over towards the very hard-to-estimate end, I would have individual stocks, crypto, highly-idiosyncratic investments – so there’s certainly a lot of things out there for which we don’t have the tools to estimate those distributions. There’s plenty of people out there whose day job is trying to estimate what’s going to happen with a single stock that they cover or a portfolio of stocks. We don’t do that ourselves, but there’s lots of people who do it and think they can do that. I’ll stop there.

JB:

Great. So, I guess we can wrap up there. A lot of exciting things – we’re excited about the second-half of the year, beyond what Victor talked about, we’re looking to host a few events. We definitely have a few things penciled into the calendar that, once we lock in, we’ll certainly let this group know. More book updates to come, including the release of the paperback. Again, not sure when that exactly will be – hopefully in time for the holidays; great stocking stuffer, certainly.

One of the one of the big questions that we hear a lot about is, how many people have enjoyed hearing about Elm on their favorite podcasts. We are very interested to learn what podcasts people listen to. So if you’re interested in sharing, please, definitely let us know. That’s that’s our our parting shot – if you’re a podcast listener, shoot me a note with your favorite podcast (jerry@elmwealth.com) and see if it’s still your favorite podcast after Victor and James appear on it.

VH:

Thanks everybody – really appreciate the attendance, the support, the trust. It’s great, and please know that you can reach out to any of the three of us with any questions or suggestions. Thank you and looking forward to seeing many of you before our next call in January.

Interested in more like this?

Subscribe to our mailing list and get notified about new Elm news and research.